The revisioning of ‘old normal’ face-to-face design education in an online environment in a short timeframe is a very wicked problem indeed. In our Faculty, ‘design’ has influenced the modes, the conceptualisation and the foci of this shift over the past semester, and our preparations for the next.

This post has been prepared by members of the Built Environments Learning and Teaching (BEL+T) group at the University of Melbourne (UoM). In it, we unpack a relational framework for moving design learning and teaching online through a sequential presentation of our Guidance for Moving Online resources and described by our DIAgram. We outline how this approach has been applied in an Australian university context, and ask what it may offer other contexts. It may be useful to consider this post alongside DDE’s Creating Distance Design Courses guide available here, which provides a valuable and complementary approach.

Institutional Context

The BEL+T group, within the Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning (ABP) is an academic group focussed on the sustained improvement of educational outcomes for built environment disciplines. BEL+T conducts research and consults with teaching staff in BE disciplines to this end. We are also very lucky to draw on group members’ design expertise while responding to the changes of context experienced this year.

ABP offered few online learning options until March of 2020. Fortunate to be located on a beautiful and historic campus, and to have access to workshops and contemporary making technologies, and to new studio spaces, the focus of design education was ‘hands on’ and ‘face-to-face’. Suddenly driven from the campus by COVID-19 and impacted by isolation and social distancing, we needed to develop ways to understand, communicate and inform new needs and approaches to this new world. This was made more complex as the same semester marked the introduction of a new LMS for the institution, challenging staff with a less familiar online environment, and further raising the difficulty level. In response, we developed and shared an initial framework on the BEL+T pages in the five-day space between the office and working from home(!). We looked for advice that would support teachers to deliver subject content, support interaction, and effectively assess online.

We simplified some of the complexity we encountered in order to communicate to teachers in those early days. Over time, early dualisms comparing synchronous and asynchronous approaches were enriched by global discussions and shared publications (including DDE blog posts), as well as local testing and development, to enrich our understandings as well as their representations. As an action-tested consensus began to emerge around effective delivery methods for the built environment and design disciplines in our Faculty, more complex and nuanced questions arrived: How can I make online learning experiences more engaging? and I’m worried about my students being disconnected from each other and our faculty – What can I do?

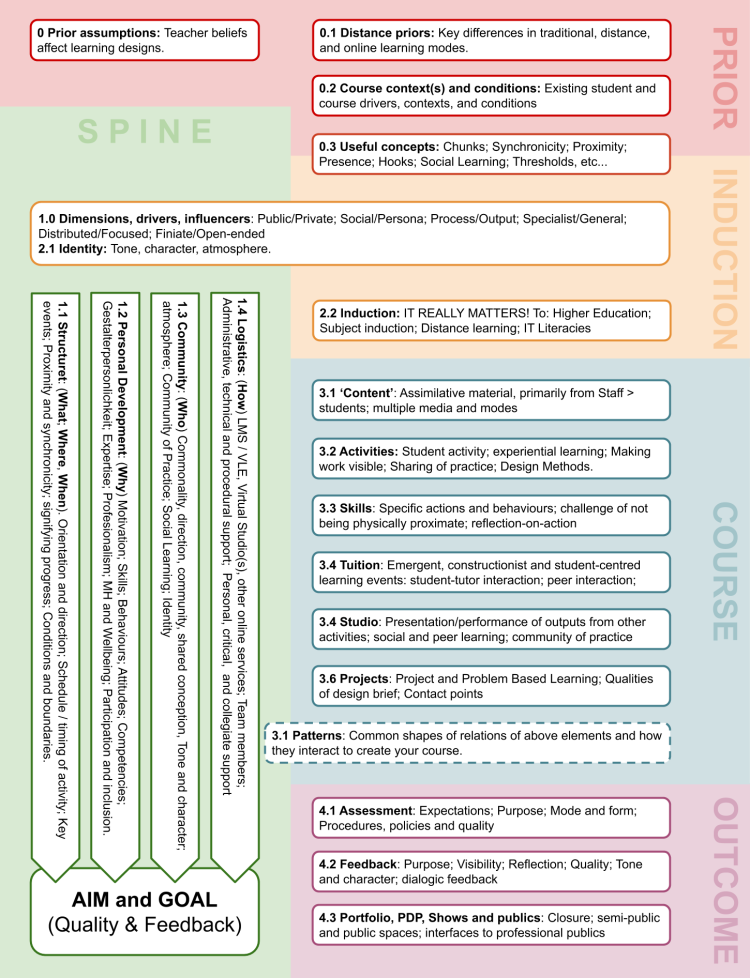

As we prepared to support a (more) planned—but still surprising— second online semester, we needed to draw together what we had learned from the Faculty’s initial move to online teaching and learning, and to translate this across multiple cohorts and programs. We needed a diagram and the ‘spatialization of a selective abstraction’ (Garcia, 2010: p.18) it offered, and to use the development and application of this tool to help make sense of the new world, to guide our actions and to evaluate their impact. The DIAgram that we designed represents the elements, influences, aims and mechanisms we identified, and continues to challenge us to consider its application for the specifics of subject area, cohort and learning aims.

Learning Engagement and Belonging : Foundational Aims

In our development of the DIAgram and the conceptual framework it represents, some foundational aims for good learning experiences, wherever they take place, remained crucial foci. These are Learning Engagement and Belonging. The significance of these is indicated by their central location in the DIAgram’s design. These foundational aims guided our daily discussions by reminding us and others that ‘what we are designing is not a product: it is the experience of that product and how that engages learning’ (Jones, 2020: p. 11).

A key prerequisite for academic achievement lies in students’ engagement with learning experiences, i.e. Learning Engagement (Kahu, 2013; van Uden et al., 2014), and the intellectual and/or emotional forms this may take (Macey and Schneider, 2008). This remains true in online environments, where ‘cognitive presence’ has been linked to academic performance (Galikyan & Admiraal, 2019). The close relationship between learning engagement, retention and motivation has been identified, and motivation highlighted as an ‘essential element to engage learners and thereby enhance students’ learning experiences’ (Gedera et al, 2015). In design, the intersection between project development and intrinsic motivation is described as ‘flow’ (Csikszentmihalyi, 1996), a linking of aim and process through these design and design learning experiences. As such, rich, personal and effective engagement with ‘learning’ as a broad activity has great overlap with an individual design student’s learning, the possibilities of a given design challenge, and the navigation of these through design practices.

Belonging refers to the attachment, reciprocity and mutual support that students feel towards various scales of community, including to their peers, teachers, institution, profession, etc. As a key contributor to a student’s overall wellbeing and ability to learn, a sense of belonging and social integration has been shown to be vital to a successful educational experience (see Baik et al., 2017; Baik et al., 2019). As the significance of connectedness is increasingly recognised, academic roles are expanding to accommodate newer expectations for pastoral care and its relationship to learning and the student experience (Laws & Fielder, 2012).

In professional disciplines, Belonging is one of the fundamental dimensions comprising occupational engagement and the development of occupational identities (Wilcock, 1999). This helps explain why the notion of ‘studio culture’ is considered inseparable from design pedagogy: ‘[S]tudio culture is meant to engender a sense of belonging among students— a feeling that they are not alone in their struggles— and between students and tutors’(Thompson, 2019: p. 22). Furthermore, ‘students use the studio as a vehicle for developing a sense of belonging to the architectural community’ (Koch et al., 2002). In the shift away from a shared physical learning environment, the move online has prompted staff to implement creative ways of fostering a sense of belonging whilst providing support across members of studio cohorts and the wider university community. It is important to remember that, ‘Studio is far more than a physical space, and it is the non- (or meta-) physical aspects of it that are worth focusing on when designing online and distance learning: the cultural, professional, personal, social, affective, etc.’ (Jones, 2020: p. 49).

We should note that Learning Engagement and Belonging, as foundational and central aims in the DIAgram, should be understood as relational concepts in the spirit of John Dewey and feminist philosophies (see Bleazby, 2013). In other words, engagement should not be conceived in service of a sense of belonging any more than we should strive to foster a sense of belonging merely to achieve learning engagement. The first, central layer of the DIAgram reflects these foundational concepts.

Delivery + Interaction + Assessment

Designing the second layer of the diagram identified a useful guide for decision-making during the 2020 COVID-19 move online. A triad of challenges for online teaching by ABP staff emerged during the move to this new environment: Delivery + Interaction + Assessment. Few academic staff of the Faculty had significant experience with teaching online. The natural tendency was for teachers to seek to replicate face-to-face practices via the virtual campus and to look for tools to do that most directly. We developed this triad model to challenge that tendency, opening initial discussions of tools and approaches to delivery, whilst integrating discussion of interaction and assessment activities. The model was initially presented in March 2020 through the BEL+T website to deliver tools for synchronous and asynchronous approaches to these activities. Subject consultations, and other global conversations, extended the approach to explore how these three factors interrelate to support and connect to the foundational aims above.

Presenting Delivery + Interaction + Assessment as an interrelated framework rather than independent parts helped to extend early lessons and developing practices, as we prepared for an anticipated (second) online semester. The intersecting representation through the DIAgram drew on early learning about changing expectations of time-planning across the week: from the relocation of a small number of ‘normal’ timetabled sessions in a Zoom environment, to more sophisticated consideration of activities and engagement that we described as a student-focused ‘workflow’ model, using the language of construction. In the DIAgram the elements are therefore overlapping, influencing and informing each other.

The term delivery refers to the learning ‘objects’ that teachers share with students. This element is represented as a ‘container’ of independent items. These might include video presentations, readings or references, studio project briefs and subject information or instructions. For many academics, Delivery of content to students was a primary early concern: How can I deliver my lectures? How can I post readings? (How) will students have access to physical sites or facilities for this subject? The DIAgram proved a useful tool to communicate that, although it may be an early concern and an easy focus for those newly ‘alone’ behind a computer screen, disseminating content to students is not an isolated or sufficient activity. Designing the links between these objects and their use online for student learning needed specific focus in the move online, and pairing delivered content and interactive activity was central to considering an overall assessment scheme. Delivery activity also aligned with the leadership or guidance role for teachers when the class was newly distributed; a brief message to students for an upcoming tutorial, whilst seemingly mundane, serves an essential role in this framework. This approach does stress, however, that delivery holds no inherent value as a teaching and learning activity. In an online space, this challenges some habits of a conventional, teacher-centred approach.

Interaction identifies the crucial opportunities for students to engage and connect with one another and/or their teachers. The DIAgram represents this as stylised figures in a circular connected group. In practice, academics explored Canvas discussion boards or Zoom meetings, and also cloud-based platforms for collaborative design projects or reviews. We distinguish between Learning Engagement which can involve students interacting with learning objects and activities, and Interaction as a human-to-human exchange of ideas or co-production of artifacts. There are two primary reasons for focusing on student-to-teacher and student-to-student interaction—relating both to Learning Engagement and Belonging. Our disciplines, whether explicitly stated in learning outcomes or not, are heavily dependent on collaborative experiences for professional development. In other words, learning to become a built environment professional is not something that happens through independent scholarship but also involves enculturation into professional, industry-specific and student communities and their discourses, behaviours and structures (Gilbuena et al., 2015). It has been suggested that design studio offers both ‘the primary space where students explore their creative skills that are so prized by the profession’ and ‘the kiln where future…designers are molded’ (Salama & Wilkinson, 2007: p. 5). Interaction across the cohort in studio, therefore, becomes central to both the student experience and to professional development.

The third element of the DIA triad, assessment, also called for a review of ‘normal’ practices in the move to an online environment. Of course, this is an area in which institutional processes and requirements influence what, how and when students might undertake assessable activities and receive feedback for learning, thereby introducing further complexity as the shift online in Australia occurred mid-semester. The intersection of Assessment decisions across the realms of ‘policy, design and judgement’ (Bearman et al., 2016: p.7) called for clear communications and frequent updates, achieved via the BEL+T website, regarding institutional changes, tool availability and use, and disciplinary values and cultures. These complexities were nowhere more challenging than in design disciplines, in which the nature of studio learning and the centrality of the final ‘design crit’ performance was of great concern—not only to consider the quality of a design proposal but as a format for students to learn some of the elements of professional performance and collaborative creativity (Tucker & Beynon, 2012). Suggested platforms and processes, including synchronous and asynchronous elements, as well as the capacity to simultaneously review a submission and critically evaluate it against a student’s claims, were all important. Considering other ways that ‘low stakes’ assessment could be incorporated within a program aimed to minimise student stresses and technology demands. The multiple paths of the Assessment element in the DIAgram indicates the importance of aligned assessment actions in students’ learning experiences.

Organisation : enabling operator

The final element of the DIAgram, Organised, refers to the ‘behind-the-scenes’ work required to coordinate and curate meaningful learning experiences for students. Effective organisation has been identified by both students and teachers as an essential foundation for valuable and meaningful learning experiences (Zehner et al., 2010), and the reduction of student attrition (Naylor et al., 2018). Again, the ultimate objective of a teacher’s organisational efforts is to enable Learning Engagement and sense of Belonging through the effective interrelation of Delivery + Interaction + Assessment activities. Our own review of student evaluations, prior to 2020, found high levels of satisfaction in subjects with strong organisational foundations, leading to a set of Tactics for Coordination that highlight the value of constructively aligned activities and assessments, clear and consistent lines of communication, and overt logistical preparations.

Organised subject delivery, particularly online, could be understood as approaching the task ‘as a designer’ as opposed to an improvisor or a dictator. Whilst those who teach design may defend some pedagogical obscurity on the basis that the nature of design learning demands ‘trust’ and ‘tolerates, even revels in, ambiguity’ (Ochsner, 2000), we suggest this conflates the design process itself with its pedagogical context. Teaching design at a distance demands organising principles that target the invisible and uncertain nature of design. Jones’ (2020: pp. 44-46) suggestion of ‘chunking’ activities in assessment deliverables, such as concept maps or reflective journals, offers a specific and applicable example.

Closing Thoughts

What might this approach and DIAgram offer to others? Like any diagram, it aims to serve multiple functions—descriptive, analytical and propositional. First, it encapsulates what we have found to be an effective conceptualisation and approach to this wicked challenge. We have found it holistic enough to capture the range of technological and pedagogical concerns arising in the move to an online learning environment, while introducing these dimensions into a productive dialogue of shared foundational aims. Importantly however, as a guiding framework, it provides flexibility rather than prescription. It specifies no scale, no time and no age group. In this way, we trust it offers value to other institutional and geographic contexts, and we hope its adaptation through further testing and development might result in newer emergent approaches.

We welcome you to visit the BEL+T Guidance for Moving Online pages where we regularly update teacher-facing content informed by this work. We also invite your feedback on our framework and DIAgram in the comments section below. We are looking forward to your thoughts!

Contact us at: [email protected]

Find us at: msd.unimelb.edu.au/belt

REFERENCES

Baik, C., Larcombe, W., & Brooker, A. (2019). How universities can enhance student mental wellbeing: the student perspective. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(4), 674-687.

Baik, C., Larcombe, W., Brooker, A., Wyn, J., Allen, L., Field, R., . . . James, R. (2017). Enhancing Student Mental Wellbeing: A Handbook for Academic Educators. The University of Melbourne: Australia.

Bearman, M., Dawson, P., Boud, D.J., Bennett, S., Hall, M.,and Molloy, E.K., (2016). Support for assessment practice: developing the Assessment Design Decisions Framework. Faculty of Social Sciences – Papers. 2378. Open access https://ro.uow.edu.au/sspapers/2378

Bleazby, J. (2013). Social reconstruction learning: dualism, Dewey and philosophy in schools. Routledge.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. New York: Harper Collins Publishers.Galikyan, I. & Admiraal, W. (2019). Students’ engagement in asynchronous online discussion: The relationship between cognitive presence, learner prominence, and academic performance. The Internet and Higher Education, 43.

Garcia, M. ed (2010). The Diagrams of Architecture. John Wiley & Sons: West Sussex, UK.

Gedera, D., Williams, J., & Wright, N. (2015). Identifying Factors Influencing Students’ Motivation and Engagement in Online Courses. In C. Koh (Ed.), Motivation, Leadership and Curriculum Design: Engaging the Net Generation and 21st Century Learners. Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-230-2_2

Gilbuena, D. M., Sherrett, B. U., Gummer, E. S., Champagne, A. B., & Koretsky, M. D. (2015). Feedback on Professional Skills as Enculturation into Communities of Practice. Journal of Engineering Education, 104(1), 7–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/jee.20061

Jones, D. (2020). Creating Distance Design Courses: A guide for educators, Distance Design Education blog: https://distancedesigneducation.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/cddc_guide_0-9.pdf

Kahu, E. R. (2013). Framing Student Engagement in Higher Education. Studies in Higher Education, 38(5), 758-773.

Koch, A., Schwennsen, K., Dutton, T. A., & Smith, D. (2002). The Redesign of Studio Culture: A report of the AIAS Studio Culture Task Force. Washington, DC: American Institute of Architecture Students.

Laws, T.A. & Fielder, B.A. (2012). Universities’ Expectations of Pastoral Care: Trends, stressors, resource gaps and support needs for teaching staff. Nurse Education Today, 32, 796-802.

Naylor, R., Baik, C., & Arkoudis, S. (2018). Identifying Attrition Risk Based on the First Year Experience. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(2), 328-342.

Ochsner, J. K. (2000). Behind the Mask: A psychoanalytic perspective on interaction in the design studio. Journal of Architectural Education, 53(4), 194– 206.

Salama, A. M., & Wilkinson, N. (2007). Legacies for the Future of Design Studio Pedagogy. In A. M. Salama & N. Wilkinson (Eds.), Design Studio Pedagogy: Horizons for the future. Gateshead: The Urban International Press.

Thompson, J. (2019). Narratives of Architectural Education: From student to architect. Routledge: Abingdon, UK.

Tucker, R., & Beynon, D. (2012). Crit Panel. In Askland, H.H., Ostwald, M.J., & Williams, A. (Eds.) Assessing Creativity, Supporting Learning in Architecture and Design (pp 133 – 156). Sydney: Australian Government Office for Learning and Teaching (OLT).

van Uden, J. M., Ritzen, H., Allen, K. (2014). Engaging Students: The role of teacher beliefs and interpersonal teacher behaviour in fostering student engagement in vocational education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 37, 21-32.

Wilcock, A. A. (1999). Reflections on Doing, Being and Becoming. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 46(1), 1– 11.

Zehner, R., Forsyth, G., de la Harpe, B., Peterson, F., Musgrave, E., Neale, D., Watson, K. (2010). Optimising studio outcomes: Guidelines for curriculum development from the Australian studio teaching project. Paper presented at the 2nd International Conference on Design Education, Sydney.

]]>In this article I would like to discuss a few of these and reflect on particular experiences from distance learning that can be helpful in countering such deficits.

I’m sure you’ve experienced this too in these strange days – Staff and students are doubly tired:

First, the amount of video conferencing has become routine in this digital summer semester.

Further, the cognitive level, which is important in design, is suffering from this strain.

How can we, as teachers, react to this situation? What historical design references can we draw on to teach design today in a sophisticated and virtual manner?

These are two key questions, the first of which I would like to explore in greater depth from a practical teaching perspective. The second question is certainly also interesting but not necessarily to be answered in the current article. Nevertheless, I would like to start with it and hope that others may contribute.

Almost 100 years ago (in the winter semester of 1919/1920, to be exact), Johannes Itten had already envisaged three dimensions in his didactics: the sensual-experiential, objectifying, and formative study. Within the Bauhaus, the learning discourse moved between these three poles until the dissolution of the university (Buchholz et al. 2007, pp. 70-73).

This early framework of Johannes Itten’s work highlights the intertwining of intellectual, emotional aesthetic, and spiritual development. Each was intended as mutual conditions necessary to the practice of design and its teaching.

Owing to an increase in instrumentalization and even commoditisation of higher education since the 1970’s onwards, we have either lost, or had to fight to retain, the sensual-experiential element in schools and universities. In Itten’s teaching, for example, it was an important ritual to do gymnastics with the students as part of a holistic curriculum, not a separate subject to be studied in isolation.

In philosophy, a similar move to understanding the world as fully experienced emerged in Phenomenology, challenging the separation of thought and experience. It was arguably Merleau-Ponty who emphasised the need to see aspects of being as fully embodied and not independent of one another: the importance of wholeness of mind, soul, and body (cf. Waldenfels 2002, p. 174). We read the physical, sensually experienced subject in a concrete and spatial situation as the reference point of the process of cognition:

One should turn to the things themselves. Not constructs and models. Otherwise, you no longer have a body-phenomenology that allows this world to emerge anew in the senses […] and has a ‘strong’ concept of experience: there is nothing ‘given’ [in the sense of ‘data’]; [experience is] not only data, but experience is a process in which the experienced person changes and the world changes as well.

Metzger 2005, 4:00-6:00, emphasis and additions in the sense of readability A. L.

These two positions confirm that a person is far more than their intellect alone: certainly more than language. However, if we think of a classical digital lecture, we have exactly this. It is through language alone—not least through the inevitable monologs of teachers—that we act in digital lectures. Thus, we forget that ‘bodies also hang’ on the digitally connected intellects, to paraphrase Merleau-Ponty.

But, in this working note, I am not only interested in integrating additional gymnastics – in reconciling the mind and body. The spirit of a person is critical too and this is where language gets in the way a bit.

In German, the word ‘leib’ means ‘more than body’, a slightly tricky concept to properly convey through literal translation. The cultural connotations of the word ‘spirit’ have already been debated editorially!). But there is an importance and value to considering matters beyond only an intersection of mind and body.

There is no need to invoke magic or other epiphenomenal matters – consider this as a cognitive phenomena, process or entity: our thinking systems (brain, cognitive structures, central nervous system, all of it). We use this whole system to think, learn and (of course) to design. It’s a complex system.

But how often do we talk about it? How often do we tell students that thinking like a designer uses a lot of your body’s energy (20-40%)? And that this is often distributed across multiple cognitive areas and systems in our minds (a different type of fatigue)? Or that learning is actually a process of physically changing your mind (another type of fatigue)? Or that mental health is cognitive health, inseparable from the rest of you?

Better mental health and wellbeing leads to better designers.

I propose that we aim to instil, encourage and foster: deeper thinking and acting in design projects that makes use of our fully embodied thinking ‘systems’ – whilst at the same time recognising the importance of looking after and caring for these same systems.

This approach should be extended to all curricular areas and made explicit in each. This recognition of holistic embodiment (mind, body, spirit) and the constellation should drive us—design teachers—to do justice in this almost pastoral responsibility.

I would like to end the working note with some practical examples an suggestions:

- Let us explicitly and programmatically take up the current discussions about yoga, meditation, forest bathing, and other techniques of embodied cognitive self-care. I have had good experience with letting students do a warm-up themselves before the lecture. These can be small exercises in progressive muscle relaxation or very specific yoga exercises. These introductory exercises help us to switch from our family or professional environment to an online lecture. Of course you can’t do this spontaneously, but it is possible to set this task as a kind of homework and then prepare individual volunteers in a private conversation.

- Let us place the everyday practises of our students in a professional framework of digital design creation. The well-established project diary can help to shed light on this increasingly important intellectual aspect of creative work. Talk actively with the students about the emotional challenges of motivation that are necessary in this peculiar semester. Make it a criterion in the project diary so that students can exchange ideas about it. The protected space of a lecture is predestined for conversations like these.

- Let us invent formats that have a personality-building effect, ‘despite’ the digital summer semester. Remember why you became a teacher? We want to accompany people on an artistic path. On this path there is a lot to see right and left, which often makes a straight path impossible. Don’t you also think that online teachers often come out too straight on the result? That we do not stop too often to address interesting issues on the way? Here it depends on a harmonious rhythm to switch between sprinting and lingering skillfully.

- Let us consider this as a challenge to contrast and compliment to handicraft design competence with ‘spiritual’ competence. This complexity is a task that in art education is traditionally regulated via the space and the people in it. In didactics for distance learning in design, which have been developed over a decade, this connection is already well developed. Throughout the operational contexts of the Corona Semester we should not forget that it is this physical complexity in design learning that is at stake.

This should also be a task for teaching design after the digital semesters that may still follow.

References:

Buchholz, Kai; Theinert, Justus; Ihden-Rothkirch, Silke (ed.) (2007): Designlehren. Wege deutscher Gestaltungsausbildung. Darmstadt University of Applied Sciences. Stuttgart: Arnoldsche Art Publ.

Itten, Johannes (1978): Gestaltungs- und Formenlehre: Mein Vorkurs am Bauhaus u. später. Ravensburg.

Metzger, Stephanie (2005): Interplay of senses and arts. Stephanie Metzger in conversation with Bernhard Waldenfels. artmix.conversation. Further participants: Stephanie Metzger. Thomas Gerwin (director): Bayerischer Rundfunk. Available online at http://www.br.de last reviewed on 24.07.2017.

Waldenfels, Bernhard (2002): Bruchlinien der Erfahrung. Phänomenologie, Psychoanalyse, Phänomenotechnik. 2nd ed. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp (Suhrkamp paperback science, 1590)

This post started out as a few reflections on a few distance design education events I attended recently, where most of the discussions did not centre around online vs face-to-face or technology and IT services. Instead, discussion focused on learning and teaching – basic stuff, like ideas around how to make learning activities engaging (for staff as well as students…).

Because that’s a messy human problem, not a technical one, Gaston Bachelard and Christopher Alexander both came up in discussions a few times. What they both have in common is their attempt to make sense of the ‘messy space between people and things’ (Koskinen et al, 2011). In research, this is where there’s too much evidence to ignore the fact that there is something going on but it’s hard to really know what this is.

This ‘messy space’ is actually a really important type of thinking that we do as designers and that we encourage in our students. But because it’s vague, difficult and valued far less than the end product, we tend to talk a lot about it and then just hope that students ‘get it’ as they experience it through designing.

Of course, that’s not much use for education colleagues who are not learning to become designers… To respond to this challenge, I’m going to use bits of science and architectural philosophy together, and hope that the two don’t cancel each other out.

At the end, I’ll get back to how this relates to distance design education – so if you’re thinking “???”, feel free to skip to the end where there’s a list.

Ideas matter more than reality

First, the science bit.

Basically, we have a load of assumptions about how we relate to the world around us – many of them are completely wrong.

Firstly, we are not perceiving machines: for example, we don’t just ‘see’ whatever we perceive through our eyes. Our visual system is composed of a number of different cognitive systems: some dedicated to specific things (such as people’s faces) and others to more general cognition (such as our ability to use spatial thinking to more than just ‘see’). Basically, our visual system, like most of our other cognitive systems, is not a single, linear or simple process – it’s complex, convoluted and recursive (Dehaene, 2020).

Secondly, that recursive loop just mentioned is critical: what we have already perceived affects future perceptions. It’s a cognitive learning process and a deeply important part of being human (i.e. Homo Sapiens). For example, we don’t see colour until we are taught what colours is – there are no universal colours such as ‘red’; it all depends on how we learn what colour is (Lotto, 2004). And that’s before we even consider how such learning is affected by our own environment and behaviours (see The Dress for an example).

Thirdly, all of this is before we take into account even higher order cognitive biases and prejudices. The famous study by Hastorf and Cantrell (1954) identified that people at the same sporting event saw things differently depending on which team they supported. Pretty obvious, you may think, but how often do we take this seriously and realise that people really do see different realities based on their preferences. You will use your biases to conceive of the world around you in particular ways and, the more you do this, the more reinforced these ideas become.

The ideas (conceptions) we construct of reality are often far more important (or ‘real’) than reality itself.

Back to virtual reality

This is why we do see evidence of ‘physical’ things happening in ‘virtual’ environments – things you wouldn’t expect to see. For example, students can report feeling claustrophobic in some architecture in virtual environments (Minocha & Tungle 2008). This example has a physical analogy in the Mémorial des Martyrs de la Déportation. In both cases, being able to only see the sky, but not the horizon, can lead to feelings of claustrophobia: in the second example this is deliberate; in the first example it was accidental.

In both, it is the conception, the idea in the mind of the person, that is common.

This is quite an extreme example of a conception in two very different environments. More usefully, conceptions can be understood as effective ways of transferring ideas. Cognitively, this is the process of thinking of a generalised version of particular things – that the word dog can refer to multiple concepts involving dog, from things with four legs to Snoopy (Dehaene, 2020): what our cognitive systems are good at is thinking at these scales of concept and then applying the most appropriate version for the given context.

But more generally, we can do this at even more abstract levels. In cognitive linguistics, these abstractions, referred to as conceptual metaphors, are where we apply some common cognition (like sense or meaning) from one concept to another. For example, we talk about ‘having’, ‘losing’, ‘keeping’ ideas even though we can’t see or touch them. Lakoff and Johnson (1980) famously constructed their embodied cognitive metaphors this way, arguing that even concepts like ‘in’ are conceptual metaphors that we transfer from one thinking domain to another. Hence, we can be ‘in’ a room but we can also be ‘in’ love or ‘in’ an organisation, or even ‘in’ trouble.

Each ‘in’ has to be understood as being related to each other. This makes it really easy to translate ideas: it’s how we can talk about really complex things, like ‘justice’, ‘home’, or ‘openness’. (This is also, potentially, one of the key ways that pluriversality can emerge, rather than the either-or of difference/universality in current dominant structures and narrative. But that’s another story…)

Making things harder

So far, we’ve mostly seen examples of transferring conceptions or using them to make complex things simple.

But sometimes we simplify things far too much:

“It is simplicity that makes the uneducated more effective than the educated when addressing popular audiences.”

Aristotle

Hence, using conceptual metaphors can be a useful way of making simple things more complex – not for the sake of making things difficult, but nuanced enough to be of utility in the design process. This might be: representative enough of complexities; open enough to allow creative divergence; communicable enough to work with others; etc.

What we’re looking for is the optimum conception for the activity at hand: not too complex and not too simple.

Any designers reading this will get it immediately: you don’t want to jump to solutions too soon; you don’t want to over-specify; you don’t want to make the problem too distributed and complex, but you don’t want it too simple either.

All good creative design processes operate in that Goldilocks space of it being not-too-simple / not-too-complex. And we (designers) have loads of tools we use to make things more or less complex depending on the circumstances and need. In doing so we are creating a space where things are both defined and not defined at the same time. Keeping this balance is really important: defined, but not too much. Undefined, but not too much.

This is not a contradiction or a fudging of what’s true: it’s a level of cognitive conception that allows contingent uncertainty (1). At some point this uncertainty will collapse (to some specific idea) but it’s a state of thinking that we can (mostly) return to at any point and rework.

In other words, our imagination is more valuable than other cognitive processes for some complex activities – we can use our imagination to define as well as create the world, not just to come up with ideas…

Back to Bachelard

Which is where Bachelard comes back in. He deliberately writes about architecture as poetry (or I should say, poetry as architecture!) because it allows the ideas he’s talking about to be both defined and not-defined at that same time. We all ‘know’ what home is; but we might not agree on what colour it should be.

Thinking like this can be exceptionally valuable because it moves from the very specific to the very general and understands how these relate, as well as their limitations. Have a read of Ritchey’s (1991) paper on how Riemann did this to understand the mathematics behind hearing.

Bachelard is using a mix of different scales of cognitive conception. In fact, much of his work could be thought of as a series of conceptual metaphors that try to communicate the human qualities of architecture: their experience and meaning (Bachelard was writing as a phenomenologist). Critically, he was conveying this as a writer so he was necessarily using cognitive linguistic metaphors.

Beyond the technical words there is a conceptual simplicity to his work. When Bachelard describes the porch, he describes the human experience of being on a porch: what it feels like; what people do (and can’t) on porches; what the world looks like from a porch. Critically, it’s not the porch itself that enables this experience: it’s the human doing the conceiving as a result of being-in the porch (non-attribution deliberate…).

That might make you wonder whether everyone, everywhere does indeed share a similar experience of porch. Christopher Alexander took this idea further but looked at it from the ground up: if we keep seeing the same shapes in architecture all over the world and across all cultures, then that suggests a deeper pattern in human behaviour. Alexander came up with a number of patterns from human settlements and the built environment and called it a Pattern Language (Alexander et al, 1977).

But, critically, Alexander recognised that these patterns needed to be defined at the right ‘scale’ – not too defined but not too vague either. In addition, he also introduced the idea of a ‘quality without name’ (2) to refer to the underlying human value of each pattern – what it is about the pattern that people value.

Teaching bit

This brings us back to teaching design at a distance. (you still here?)

The discussions I referred to at the start have done a similar thing. Firstly, they focused on the human value and purpose of what we intend by design education. Secondly, they use a range of scales of metaphor to discuss this, something designers are particularly good at (a two line sketch can represent The Infinite Void or a soap dispenser…).

So I suppose that what’s finally useful is to explicitly recognise and acknowledge the value of this type of thinking, knowledge and discussion. In fact, to promote its value beyond discipline conversations and use it actively to engage with others (we already do this, but perhaps don’t realise it). Especially when thinking about what you need to teach at a distance.

So here’s the List of Fun Things to Try with Conceptual Metaphors:

- Start with conceptions, not solutions or tech. Instead of saying ‘I need a Virtual Design Studio’, ask yourself what the studio space should feel like (using conceptions). What is the ‘quality without name’ you’re looking for (just because you can’t name this it doesn’t mean you can’t describe it)? Have a look at the dimensions listed here for ideas and use these to brief, specify and discuss requirements with others. You do not have to fall into the trap of using reductive tech language to ask for what you need for your students.

- Use conceptual metaphors, not tech names. Someone else mentioned this at the CHEAD event, but to call a lecture a ‘Webinar’ is to deliberately draw attention to the technical medium. We don’t call seminars ‘f2f-inars’ … (OK, clunky example…). If an event is a tutorial then it’s OK to call it a tutorial regardless of where and how it’s arranged – it’s the human value that’s more useful to communicate than the medium or mode.

- Make some key things more complex, not less. If you need a particular atmosphere or feeling (a ‘quality without name’) in your studio or class then state that clearly. Be confident about your uncertainty – describe this as boundaries of knowledge rather than just ignorance (you’re technically an agnotologist). But don’t hide it either – be open about how we use uncertainty with colleagues and especially students (give them something solid if they need it).

- Be critical and reflective when you do this. I haven’t touched on the dark side of this type of cognition (it can be very dark indeed) so make use of the other major tool in our design toolkits – our ability to evaluate the process at the same time as engaging in that process. Using some simple, critical frames to help you critique from other perspectives.

Anyway, I hope that made some sense. Not sure if it all got a bit out of hand at one point but it ended with a list, so maybe it’ll be fine…

Notes

(1) Cognitive uncertainty may have analogies to, or even be a form of, of cognition-as-optimisation theories (error reduction; reward optimisation; etc.), where the fuzziness of uncertainty is used in conjunction with other cognitive feedback processes to ‘get to’ some cognitive resolution.

(2) This ‘quality without a name’ has been thoroughly criticised for good (and bad) reasons, so to give it a bit of life here I’ll suggest that it is “an appropriately scaled cognitive conceptual gestalt (or conception) interrelated with human experiences and phenomena that operates with sufficient similarity across large numbers of peoples to be evidenced in their constructed artefacts and habits”. Gaston would be horrified.

References

Alexander, C., Ishikawa, S., Silverstein, M., Jacobson, M., Fiksdahl-King, I. and Angel, S. (1977) A Pattern Language, 1st edn, New York, Oxford University Press.

Hastorf, A. H. and Cantril, H. (1954) ‘Case reports. They saw a game: a case study’, The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, vol. 49, no. 1, pp. 129–134.

Koskinen, I., Zimmerman, J., Binder, T., Redström, J. and Wensveen, S. (2011) Design Research Through Practice, 1st edn, Waltham, Elsevier Inc.

Lotto, R. B. (2004) ‘Visual Development: Experience Puts the Colour in Life’, Current Biology, vol. 14, pp. R619–R621.

Oldenburg, R. (1999) The Great Good Place: Cafaes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community, Da Capo Press.

Ritchey, T. (1991) ‘Analysis and Synthesis On Scientific Method – Based on a Study by Bernhard Riemann’, Systems Research, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 21–41 [Online]. DOI: 10.1002/sres.3850080402.

]]>This article is based on an online presentation delivered on 22 May 2020 for the Teaching Architecture Online: Methods and Outcomes seminar, organised by Curtin University and Özyeğin University, titled ‘Responsive Ecosystems for Architectural Education’ (Morkel & Delport, 2020). In this article, we propose that, rather than the on-ground-online binary, architectural education might be conceived as an ecosystem-of-learning. We further suggest that this ecosystem-of-learning can be explored through the testing of random concepts to prompt and provoke a shift in thinking.

Introduction

Covid-19 exposed the fragility of schools of architecture, affecting carefully integrated curricula, student experiences and teaching methodologies. We position this integrated learning approach as an ecosystem-of-learning comprised of a number of elements including those shown in Figure 1.

Social distancing forced some parts of the default ecosystem to change drastically and suddenly, and this impacted on the entire ecosystem-of-learning. Access to physical buildings, studios, and workshops was lost. The place dimension of the learning system changed (figure 2). Where, before, time was carefully divided into segments on a timetable, organising the occupation of physical space, suddenly the timetable itself became obsolete.

‘Higher education institutions must prepare for an intermediate period of transition and begin future-proofing for the long term’ proposed DeVaney et al. (2020). So we’re asking: how might we shift our gaze to the longer term, to move online architectural education beyond “emergency remote teaching” (Hodges et al., 2020), from ‘contingency to sustainability’ (Salmon, 2020)?

Yet, what we’ve observed in webinars, blog posts, forums and research writings over the past number of weeks, are questions asked about the uncertainty and unpredictability of the situation. In the process of adapting to a new condition, there’s a degree of vulnerability, concerns arising over inequality and access, the loss of touching paper, building models, the physical making together, the incidental moments of discovery, the informal and social learning instances, the camaraderie and the fun – these experiences have been ‘lost’ through mandatory social distancing and the resultant altered dimensions of space and time.

Is a reset possible?

Darren Ockert (2020) writes that ‘(e)ach day during the pandemic, we are suddenly finding what was once impossible is now suddenly possible.’ He quotes Thomas Friedman, who said of online learning in 2012 ‘Big breakthroughs happen when what is suddenly possible meets what is desperately necessary.’

We believe that a reset is possible, but through ‘step(ping) beyond the obvious and rethink(ing) how we think’ (Weyler, 2020).

What next?

To use the crisis as a catalyst for innovation, as suggested by O’Reilly (2020), we turn to the ecosystem-of-learning as a metaphor. An environmental ecosystem is defined as a ‘complex of living organisms, their physical environment, and all their interrelationships (are) in a particular unit of space’ (Merriam-Webster, n.d.). Considering learning as an intrinsically human activity that occurs in many places and in different ways (Rustici, 2018) we conceptualise an ecosystem-of-learning that involves the tools, technologies, resources, the people and the places where learning happens.We chose ecosystem over ecology as a framework because, compared to ecology which describes a universal idea, an ecosystem is associated with a specific context (Merriam-Webster, n.d.).

A different way of thinking might embrace diversity in the way that Rex Weyler (2020) suggests: ‘Diversity remains a value in an ecosystem because diversity enhances stability.’ He further explains that ‘an ecosystem prospers if it is simultaneously stable and flexible, conservative and progressive’ (Weyler, 2020).

To demonstrate how a shift in thinking might be prompted, we draw on a range of random concepts to generate questions (Hitge, 2016; Kayton, 2011). These questions are borrowed from six domains, as thinking prompts, to reshape architectural education for the future. The selected domains are educational, economic, environmental, social, technological and political domains; each explored through three randomly selected conceptual question prompts.Of course the question prompts and resulting exploration will have varying results, depending on the participants. For example, some prompts may be more relevant to management, others to faculty or students. Furthermore, for each of the prompts (the list is not extensive), different viewpoints should be taken.

In a recent online lecture, entitled ‘How Limitations Boots Creativity’ Ingwio D’Hespeel from the LUCA School of Arts in Belgium, reimagined the traditional PowerPoint and presented his talk with a ‘paperpoint’. The low-tech, low-budget and low-resource paperpoint brings aspects of the interactive and the hand-made into the online space.

We hope that the thematic conceptual prompts that we introduce below, can trigger similar creative, relevant and realisable reactions to inspire the development of a responsive and resilient ecosystem-of-learning for architectural and design education.

Educational prompts

How might pedagogy of care, universal design for learning and flux pedagogy help us shift our thinking towards a responsive, resilient and relevant ecosystem-of-learning for architectural education in these times of change, uncertainty and unpredictability?

- Pedagogy of care is a concept that stresses contribution and empathy. Cormier (2020) asks ‘how can we balance the care that we give our students and the care that we give to ourselves?’ He invites us to imagine the first five minutes of class – the smiles, the eye-rolls and the catch-ups, and to think about ways to do that online.

- Universal design for learning, according to Morin (2020), ‘is a way of thinking about teaching and learning that gives students an equal opportunity to succeed’, through the flexible use of a variety of teaching methods to remove any barriers, and respond to every student’s strengths and needs.

- Flux pedagogy is a term recently coined by Sharon Ravitch (2020), and it integrates ‘relational and critical pedagogy frameworks into a transformative teaching approach in times of radical flux.’ She explains that it is ‘a humanizing pedagogy that examines the goals and processes of education in moments of uncertainty with a goal of mutual growth and transformation.’ Also, refer to Beatty’s (2019) Hybrid-Flexible (HyFlex) Course Design.

Economic prompts

How might sharing economy, phygital marketing and the gig economy help us shift our thinking towards a responsive, resilient and relevant ecosystem-of-learning for architectural education in these times of change, uncertainty and unpredictability?

- Sharing economy. The sharing economy or Uberfication marks a prominent ‘societal shift’ in which ‘state-regulated service providers like hotels and taxi companies, are replaced by information and data management intermediaries, like Airbnb… and Uber’ (Hall, 2015).

- Phygital marketing. Phygital (also known as phygital) merges the ‘online and offline environments’, taking the ‘best aspects from each space to create an improved customer experience.’ For example, using technology on multiple platforms to build on the ‘immediacy, immersion, and interaction’ of the real bricks and mortar experience (Ames, 2019).

- Gig economy. The concept of the gig economy has been around for a while, with specific reference to the manner in which people work. It can be broadly defined as “a labour market made up of freelance, short-term and on-demand work…which…redefines the way companies hire and how individuals structure their careers (Investec, 2019).

Environmental prompts

How might regenerative design, permaculture design and environmental sociology help us shift our thinking towards a responsive, resilient and relevant ecosystem-of-learning for architectural education in these times of change, uncertainty and unpredictability?

- Regenerative design, which, as a general concept, is a ‘principle that calls for products or services to contribute to systems that renew or replenish themselves. This ultimately means the materials and energy that go into a product or process, can be reintroduced into the same process or system, requiring little to no inputs to maintain it’ (Wbcsd, 2020).

- Permaculture design, although far from a new concept, has 12 key principles that ‘opens into whole systems thinking’ and are ‘thinking tools, that when used together, allow us to creatively re-design our environment and our behavior in a world of less energy and resources’ (Holmgren and Telford, 2020).

- Environmental sociology is concerned with the ‘reciprocal relationships between environment and society.’ The concept acknowledges that ‘environmental issues (we could also read here educational issues) are socially constructed in ways that need to be understood if effective and just strategies for dealing with them are to be found’ (Lockie, 2015:139).

Social prompts

How might fun theory, social presence theory and compassionate collaboration help us shift our thinking towards a responsive, resilient and relevant ecosystem-of-learning for architectural education in these times of change, uncertainty and unpredictability?

- Fun Theory. If you want to get people to change their behaviour you must make what you want them to do, novel and fun, according to Wickes (2018). That’s Fun theory – it’s as simple as that.

- Social presence theory. Social presence theory (presence vs attention) is used to understand how people socially interact in online learning environments. Researchers like Whiteside, Dikkers and Swan (2017) define social presence in terms of being a “real” person, where others define it as feeling a connection or sense of belonging with others.

- Compassionate collaboration. Sir Ken Robinson refers to compassionate collaboration and he means compassion that is ‘fundamental to our ability to be together as communities, as the sort of cultural glue that holds us together …’ (Hall, 2017).

Technological prompts

How might human-computer interaction, bioinformatics and makification help us think about a responsive, resilient and relevant ecosystem-of-learning for architectural education in these times of change, uncertainty and unpredictability?

- Human-computer interaction. Dickson (2017) posits that “(t)hanks to advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning, a slow but steady transformation is coming to education…’ and he says that it forces us to consider what it means to be human.

- Bioinformatics. Ben Williamsen (2020) references socio-genomics and geno-economics that link the study of genomics with predicted socio-economic outcomes through the power of big data and bioinformatics infrastructures.

- Makification. Cohen, Jones, Smith & Calandra, (2017:3) writes that ‘simply put, we define makification as the process of taking characteristic elements from the maker movement and infusing them into formal educational activities in a variety of contexts.’

Political prompts

How might cultural citizenship, development theory and the entrepreneurial state help us shift our thinking towards a responsive, resilient and relevant ecosystem-of-learning for architectural education in these times of change, uncertainty and unpredictability?

- Cultural citizenship. According to Van Hensbroek, ’cultural citizenship, psychologically and ideologically connects members within a community, or members of different communities through a sense of common belonging, reciprocal recognition of belonging, and shared experiences of daily life’ (Van Hensbroek, 2010: 317).

- Development theory. ‘Development theory is a collection of theories about how desirable change in society is best achieved’ (Gallagher, 2016: 260).

- The Entrepreneurial State. In her controversial book, ‘The Entrepreneurial State’, Mariana Mazzucato reveals that, contrary to popular belief, the state is, and has been, our boldest and most valuable innovator, e.g. in the pharmaceutical industry. Almost every medical breakthrough starts in publicly funded laboratories.

Conclusion

As the emergency subsides but normality fails to return, higher education institutions must consider a reset. There’s a good likelihood that virtual learning – in some form or another – will be part of education for the foreseeable future. Coalescent spaces for learning are inevitable (White, 2016), but exactly how this plays out, will depend on the degree to which we are able to rethink and reconceptualise the different elements of the ecosystem and how they relate.

We hope that our exploration will prompt further thinking and debate towards a responsive, resilient and relevant ecosystem-of-learning for architectural education in these times of change, uncertainty and unpredictability. Considering architectural education as an ecosystem-of-learning can help us move beyond the on-ground-onsite binary towards a dynamic but balanced, ecosystem.

This is work in progress and we invite your comments and suggestions.

Postscript

We both studied at a traditional University in the Eastern Cape of South Africa. The University of Port Elizabeth was, at the time, operating very much like most universities today, although we graduated even before the computer made it into architecture as a tool for drawing. After a few years in practice, we both started teaching, almost at the same time, at the Cape Technikon. There, architecture was taught from a technological perspective, so, from the start of our academic careers, we taught differently to how we had been taught. We both started writing about our teaching practices when the Technikon became a University and formal research was introduced, focusing on alternative places of learning (other than the studio). We tested our respective research ideas in the second year studio, where students were involved in academic and work-based learning components. Starting in 2010, together with our students, we crafted this studio into an online and onsite model to expand the on-campus studio. The online explorations included learning through digital storytelling, wayfinding using QR codes, virtual tutors, etcetera. During the block weeks, we met physically with our students, where they participated in interactive and hands-on exercises, such as experimenting with natural building methods, developing designs through physical model building and completing design-build projects in communities. In-between the block weeks, students were supported at their places of work, online, through various social media platforms, a course blog, feedback via podcasts and screencasts, reflection through blogging, and online desk crits using skype. These ideas led to other blended and online programmes, for example, the part-time BTech programme offered by the CPUT in collaboration with Open Architecture.

*Dr Hermie Delport is the Programme Leader: Architecture and Spatial Design at STADIO Holdings

The diagrams

In our search for literature on ecosystems, after we had formulated the ecosystem diagrams (figures 1, 3 and 4), we serendipitously found the Sacramento startup and innovation ecosystem diagrams (Bennett, 2016). The potential of this ‘circuit board diagram, aka subway map’ diagramming method to describe and compare ecosystems-of-learning, should be further explored.

References

Ames, C. 2019. Blurring the line between Physical and Digital. https://www.emotivebrand.com/phygital/

Beatty, B. J. (2019). Hybrid-Flexible Course Design: Implementing student-directed hybrid classes (1st ed.). EdTech Books. Retrieved from https://edtechbooks.org/hyflex

Bennet, J. 2016. Sacramento startup and innovation ecosystem diagram update. [online]. Accessed via https://startupsac.com/sacramento-startup-and-innovation-ecosystem-diagram-update/

Bregman, R. 2020. The neoliberal era is ending. What comes next? https://thecorrespondent.com/466/the-neoliberal-era-is-ending-what-comes-next/61655148676-a00ee89a

Cohen, J., Jones, W.M., Smith, S. & Calandra, B. 2017. Makification: Towards a framework for leveraging the maker movement in formal education. Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia. 26(3):217–229

Collins Z., Holum A., Seely Brown J. 1991 Cognitive Apprenticeship: Making Thinking Visible http://www.21learn.org/archive/cognitive-apprenticeship-making-thinking-visible/

Cormier, D. 2020. Move to Online Learning: 12 Key ideas. Move to Online Learning: 12 Key Ideas – Dave’s Educational Blog http://davecormier.com/edblog/2020/05/17/move-to-online-learning-12-key-ideas/

Costanza, R., Mageau, M. 1999. What is a healthy ecosystem?. Aquatic Ecology 33, 105–115 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009930313242

DeKay, M. 1996. Systems thinking as the basis for an ecological design education. Proceedings of the 21st National Passive Solar Conference. Systems Thinking as the Basis for an Ecological Design Education. School of Architecture Washington University St. Louis.

DeVaney, J. Shimson, G. Rascoff, M. and Maggioncalda, J. 2020. Higher Ed Needs a Long-Term Plan for Virtual Learning. Harvard Business Review. [online]. Available at: https://hbr.org/2020/05/higher-ed-needs-a-long-term-plan-for-virtual-learning

D’Hespeel, I. 2020. How Limitations Boots Creativity. Online presentation on 20 April 2020, Greenside Design Centre Lockdown lecture series.

Dickson, B. 2017. How Artificial Intelligence Is Shaping the Future of Education. https://www.pcmag.com/news/how-artificial-intelligence-is-shaping-the-future-of-education

Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/ecosystem

Gallagher, S. 2019. Banking Performance and Socio Economic Development. ED – Tech Press, Essex.

Hall, G. 2015. Post-Welfare Capitalism and the Uberfication of the University II: Platform Capitalism. http://www.garyhall.info/journal/2015/4/28/post-welfare-capitalism-and-the-uberfication-of-the-universi.html

Hall, R. 2017. Surviving in the Modern World: In conversation with Sir Ken Robinson. https://www.ashoka.org/en-gb/story/surviving-modern-world-conversation-sir-ken-robinson

Hitge, L. 2016. Cognitive apprenticeship in architecture education: using a scaffolding tool to support conceptual design. University of Cape Town.

HMC Architects, 2020 https://hmcarchitects.com/news/regenerative-architecture-principles-a-departure-from-modern-sustainable-design-2019-04-12/

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T. and Bond. A. 2020. The Difference Between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning. Educause Review. [online] Available at: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning

Holmgren and Telford. 2020. Permaculture Principle [online] Available at: https://permacultureprinciples.com/principles/

Investec. 2019. Rocking the gig economy [online] Available at: https://www.investec.com/en_za/focus/economy/rocking-the-gig-economy.html

Lederman, D. 2020. The HyFlex OPtion for Instruction if Campuses Open This Fall. [online] Available at: https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2020/05/13/one-option-delivering-instruction-if-campuses-open-fall-hyflex

Lockie, S. 2015. What is environmental sociology?. Environmental Sociology 1:3, pages 139-142. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23251042.2015.1066084

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Ecosystem. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved June 1, 2020, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ecosystem

Morin, A. 2020. What is Universal Design for Learning (UDL)? https://www.understood.org/en/learning-thinking-differences/treatments-approaches/educational-strategies/universal-design-for-learning-what-it-is-and-how-it-works

Morkel, J. and Delport, H. (2020). Responsive Ecosystems for Architectural Education. Online presentation for the Seminar Teaching architecture online 2. Methods and outcomes, 22 May 2020. [online]. Available at: https://youtu.be/q5y6puwYFng [31 May 2020].

Ockert, D. 2020. What Coronavirus can Teach Architecture Schools about Virtual Learning. https://www.archdaily.com/938784/what-coronavirus-can-teach-architecture-schools-about-virtual-learning

O’Reilly. 2020. Don’t let a good Crisis go to waste. Instead use it as a catalyst for innovation. https://singularityhub.com/2020/05/03/dont-let-a-good-crisis-go-to-waste-instead-use-it-as-a-catalyst-for-innovation/

Patrick Kayton – Going With The Flow (2011) YouTube video added by TEDxCapeTown Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r8T7FYTiXKI [Accessed 1 June 2020].

Ravitch, S. 2020. Flux pedagogy. Transformative Teaching in the time of Corona. [online] Available at: https://www.methodspace.com/flux-pedagogy-transforming-teaching-learning-during-coronavirus/

Rustici, M. 2018. An Introduction to Modern Learning Ecosystems. https://www.watershedlrs.com/blog/learning-data-ecosystems/what-is-a-modern-learning-ecosystem

Salmon, G. 2020. Covid-19 is the pivot point for online learning. Whonke. [online] Available at: https://wonkhe.com/blogs/covid-19-is-the-pivot-point-for-online-learning/?fbclid=IwAR3vxMkUXrOTwqqE2aVdeJghoNb3PIyGLVT2UsqBMS4heNUs8SFY5cQAiq4

Steward, S. 2020. Five Myths about the Gig Economy. The Washington Post [online]. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/five-myths/five-myths-about-the-gig-economy/2020/04/24/852023e4-8577-11ea-ae26-989cfce1c7c7_story.html

Tomboc, K. 2019. What is Information Design. https://www.easel.ly/blog/what-is-information-design/

Van Hensbroek, PB. 2010. Cultural citizenship as a normative notion for activist practices, Citizenship Studies, 14:3, 317-330, DOI: 10.1080/13621021003731880

Wbcsd. 2020. Circular Economy Programme. [online] Available at: https://www.ceguide.org/Strategies-and-examples/Design/Regenerative-design

Weyler, R. 2020. Ecological imperatives – we can’t keep growing like this, [online] Available at: https:www.greenpeace.org/international/story/43513/ecological-imperatives-growth-economics-coronavirus-pandemic/

White, D. 2016. Coalescent spaces http://daveowhite.com/coalescent/

Wickes, S. 2018. https://www.familyadventureproject.org/fun-theory/

Williamsen, B. 2020. Datafication and automation in higher education during and after the Covid-19 crisis https://codeactsineducation.wordpress.com/

]]>It took a bit longer than expected (it started out as a blog post but ended up being a 20k word monster!), so there’s a few ways you can use it set out below.

Over the next few weeks I’ll think about other ways to make expand on it and make it more widely available – so any suggestions on this would be welcomed (e.g. blog posts on topics; videos; discussions/debates; workshop sessions; ? ). Just let us know ([email protected]).

Ways to use the guide.

If you already have a course ready for online and distance delivery, you might simply use this guide as a check or list of things to think about. Here’s a map of the contents:

If you have an existing blended course or are experienced and confident in blending modes of learning, you might simply want ideas and ways of thinking about parts of your course. In this case you can refer to individual sections based on what interests you (see map above).

If you need to re-plan an existing course, the chances are your overall structure and direction are fine but that you might need to focus on the transition (or transposition) to online and distance. Focusing on sections 0 Priors and 1 Spine and 2 Induction will likely be of most use to you here).

If you’re needing to start from scratch then, by all means, use the guide to do this (as a structure or as some way to begin the design process). But think about connecting with someone or a community to support you in doing this.

As always, if anyone has any feedback on the Guide or any suggestions of what else would be of help then please just get in touch ([email protected]).

]]>At the time of writing, in early May 2020, most architecture educators have passed through all five stages of the Kübler-Ross model of grief: denial, anger, depression, bargaining, acceptance (Kübler-Ross, 1969). We spent the first two months of the year in a politically-sanctioned period of denial. When it became apparent that the virus was not contained to a specific geographic region or demographic, our governments instigated restrictions and our universities closed. At that point, we entered the phase of anger. Some made it to bargaining and then depression. Those who made it out the other side are emerging with a lukewarm glow of acceptance: we are all distance educators now.

Researchers at Imperial College London have argued that we need two different but interdependent strategies to manage the effects of the virus: mitigation (slowing epidemic spread while protecting those most at risk) and suppression (reversing epidemic growth and maintaining that situation indefinitely) (Ferguson et al, 2020). If followed, the Imperial College model is sobering for teachers. We can expect at least three, perhaps four, periods of social distancing during the northern hemisphere’s 2020/21 academic year – and that’s assuming we return to campus at all.

As we approach the busiest days of the academic year in the northern hemisphere, we have to recognise a fundamental fact: “we’re not going back to normal” (Lichfield, 2020).

The shift to distance education presents a particular challenge for architecture education. Our discipline has been one of the most resistant to fundamental pedagogical change. With fairly dramatic change now imposed upon us, and as our focus shifts from just surviving this year to actively planning next year, there is an opportunity to critically engage with the widely held assumptions of how we teach design in architecture.

Our signature pedagogy

In the United Kingdom, the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) and the Architects Registration Board (ARB) administer the discipline’s professional accreditation. The RIBA Procedures for Validation and Validation Criteria have, since their revision in 2011, explicitly prescribed that the assessed work of undergraduate and taught postgraduate courses in architecture “should consist of at least 50% design studio projects” (RIBA, 2014, p. 5). Not design projects, but design studio projects. The gatekeepers of the profession in the UK specify not only a minimum quota of design education but also an inconsistently interpreted method of delivery.

A survey of the 63 validation reports of UK architecture schools published by RIBA between 2014 and 2019 finds 25 instances of references to “studio culture”, either in the commendations by the board that visited the school of the academic position statements written by the heads of schools.[1]

These academic position statements include phrases such as “central to our programmes is a strong and vibrant studio culture,” (RIBA, 2017a, p.4) and “in our studio culture we experiment playfully, analyse thoughtfully, apply rigorously and reflect critically… Studio culture provides the safe, inclusive environment in which students can take risks and increase in confidence.” (RIBA, 2020, p.4)

Another statement reads that “central to the ethos of the school is the vibrant studio culture, which is the foundation of the student experience and emphasises a culture of the craft of making integrated with digital design … Design studio is seen as a place for the exchange of ideas where students learn from each other as well as staff and visiting scholars and practitioners.” (RIBA, 2016, p.3)

The design studio is clearly a pervasive learning environment. It is also one that absorbs students far beyond their scheduled contact hours. One school writes how “the 24-hour access to these studios plus the open kitchens has engendered a strong connection between students on all programmes.” (RIBA, 2017b, p.4) Likewise, the commendations of another report congratulate a programme team for inculcating students to treat the studio not just as a place of study, but a place of continuous occupation, where (with my emphasis) “students in the school had unselfconsciously created a genuine live-in studio culture in their main building.” (RIBA, 2017c, p.6)

In these documents we can see how the design studio can be variously celebrated as “a place to study and work in a highly creative multi-disciplinary environment alongside dance, art, design and music studios” (RIBA, 2018, p.3) or criticised as a dangerous site of intermingling with non-architects. The action point of a report observes (with my emphasis) “that the social and cultural environment of architecture in the studios needed to be carefully nurtured, and that too much diffusion of the subject area across the campus might have unintended consequences.” (RIBA, 2017c, p.6)

The design studio is architecture’s signature pedagogy. Lee Shulman defined the concept of signature pedagogy as “types of teaching that organize the fundamental ways in which future practitioners are educated for their new professions.” The design studio in the architecture school is a perfect example of how, Shulman writes, signature pedagogies “even determine the architectural design of educational institutions, which in turn serves to perpetuate these approaches.” (Shulman, 2005, p.54)

Yet the design studio is a complex and multi-dimensional thing. It is the site of both innovation and uncritical replication. It is home to both critical pedagogies that liberate students and uncritical teaching methods which demand their submission to old fashioned ways.

The four dimensions of the design studio

One way to understand the design studio, it is necessary to comprehend what I call its four characteristic dimensions. These dimensions are related to but distinct from the four learning constructs of studio education that Donald Schön described in Educating the Reflective Practitioner (1987): a physical space or constructed environment for learning and teaching; a mode of teaching and learning; a program of activity; and a culture, created by students and studio teachers working together. Schön writes how the design studio is defined by any one-or-more of these constructs, but I would argue that the four cannot be considered in isolation.

Firstly, the design studio is a physical space in the now-shuttered campuses of higher education. How many other disciplines continue to defend the right of an undergraduate student to be provided with their own desk and a working environment on campus, twenty-four-seven for the duration of their studies? In many institutions, therefore, it is the site of a conflict between the traditions of the discipline and the economic pressures of the contemporary university.

Many recent reactions to the shutdown of higher education have come from those educators who regard the space of the architecture design studio as fundamental to the “slightly odd” teaching methods of architecture education. Published in the weeks immediately following the lockdown, one architecture educator writes that “our students rely on having physical and intellectual spaces on campus in which to work. They need access to a well-lit, well-resourced model-making workshop. They require computers they cannot afford themselves. They need each other — students need to be able to rely on their peers if their home environments don’t support our much-loved but slightly odd pedagogical methods.” (Lappin in Sadler et al, 2020)

Secondly, the design studio is a period of time in the teaching calendar. With continuous access to their own learning space, the timetable of an architecture student before the coronavirus pandemic will have also included one or maybe two days per week that were simply ascribed to “studio” – the indeterminate catchall for the time when a student is expected to be present and engaging in either self-directed or directed learning. Many schools of architecture have interpreted the RIBA validation condition of fifty per cent of the curriculum being delivered through design studio to mean that fifty per cent of a student’s schedule must be designated as “studio” time.

In recent weeks, architecture educators who have described their adaptation to “pandemic teaching” have mourned the loss of this collective time. Despite invoking Jeremy Bentham’s eighteenth-century prison one educator writes:

The design studio, however panoptical, offers more than a physical infrastructure that allocates equal desktop space. It offers common hours through which skills sets, expertise, energy, motivation and/or inspiration are in constant flux and are thereby permanently redistributed. A shared studio impedes sorting into the haves and have nots … The very physicality of studio space enables regulation of common standards against the logic of competition … just as the fixed parameter of 12 studio-hours per week can help level the ground between those rich in hours and those disadvantaged by day-jobs or dependents. (Roddier in Pries et al, 2020) [2]

Thirdly, the design studio can be understood as a large field of both teaching method and pedagogies. These are not the same thing. Within the indeterminate time ascribed to “studio” in the calendar, anything goes. The more creative and critical architecture educators deliver radical pedagogical activities, teaching that is informed by educational theory and political agenda. These include collaborative workshops, peer-to-peer learning, blends of asynchronous and synchronous teaching, flipped classroom exercises, experiential learning or live projects with real clients to name just a few. Yet in the darker corners survives the studio where students endure the same old corrupt banking model of education that the tutor learned about as a student. This approach relies on repetition, replication and duplication, and I would argue this distinguishes it as a teaching method rather than a pedagogical approach.

The fourth and final characteristic dimension of the design studio is its culture. When he proposed at is a learning construct, Schön was referring to the ideas, customs and behaviour that occurs in design studio. We should not forget the other meaning of culture: the cultivation of things like bacteria or cells in an artificial medium. Things grow, both good and bad.

The prejudices of architecture education