The presentation was based on the work presented in the article BEL+T designs a DIAgram … a relational framework for teaching online, outlining both the vision of the team as well as the tactics they used to support change in practice and thinking about supporting student learning.

Well worth a watch and the full recording is here:

The next Meetup will be on 27 October 2020, Atlantic Time (ics file), when Robert O’Toole will talk about Warwick University’s move to online and distance learning using online design tools.

See you then!

]]>Serve to:

All design educators

Time:

One minute

Cost:

Your time

Difficulty:

Easy

Background

Perhaps you, like me, have always taught and presented at conferences in a standing position. As it turns out, how we use our bodies is as important in online interactions as it is in face-to-face situations. It took me a pandemic to fully appreciate this.

This is a deceptively simple recipe that I learned only after a few awkward online teaching sessions and virtual conference presentations. During the lock-down in New Zealand in March-April 2020, I managed to setup a working space from home that included a desk with a PC plugged to two screens, and a small couch where I read and occasionally use my laptop. So, when it came to teaching and presenting in conferences, my default choice was to do these things while sitting down.

The first sessions felt awkward for a number of reasons. In one class with 60+ students we had the videos turned off, so I was talking to a screen with minimal feedback except some emojis in the chat area. Even with smaller groups where it was possible to see their faces and hear their voices, after a two-hour session something felt odd. The best way to describe it is that I felt as if I was again starting to teach and the twenty years of experience had vanished.

In one of the sessions, I decided to stand up. This seemingly simple change changed everything.

It was only then that I made the connection: Of course! Teaching is something I have always done not only standing, but walking, pacing along the stage or around the studio. By standing up, I felt at ease again while teaching and presenting, and only then I realised how extremely awkward it is for me to try and present my research or teach a topic sitting in a chair.

I am aware that this recipe has an ableist angle, but a way to think about this is: When transitioning from f2f to online interactions, reflect on what bodily experiences you can maintain, as it may surprise you how unaware you had previously been to how they are a fundamental part of how you perform and behave.

Ingredients

- A means to reposition your webcam

- (Pants)

- A lapel or lavalier microphone, if possible

Method

- Easiest recipe ever: when teaching or presenting online, stand up. That’s it.

- This will bring back some familiarity removed by the transition to virtual.

- If you can, get a wireless mic or one with a long cable, so you can move around if you want.

- That’s it!

Notes on ingredients

Obviously, great ideas have been written about the lived body, here is one that I think is particularly accessible and relevant for designers: https://doi.org/10.1145/2442106.2442114

We also recently characterised the importance of physical and social contact in the teaching of creativity here: https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2019.1628799

I’m currently collaborating with roboticists in a project on Kinaesthetic Creativity, feel free to contact me if that’s a topic of your interest.

Other flavours:

Reflect on how you dress, what habits you follow before/after a session, the idea is to pay attention to the new situation, rather than mindlessly land in situations by inertia.

Warnings:

I have made the mistake of using the laptop mic while presenting, which meant that the volume levels varied when I moved even a few inches away from the computer. To avoid this, use earphones or a more professional microphone that adjusts the volume as you move.

References

Svanæs, D. (2013). Interaction design for and with the lived body: Some implications of Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI), 20(1), 1-30. https://doi.org/10.1145/2442106.2442114

Sosa, R., & Kayrouz, D. (2020). Creativity in graduate business education: Constitutive dimensions and connections. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 57(4), 484-495. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2019.1628799

]]>Serve to:

Studio instructors

Time:

A couple of hours to a few days

Cost:

Your time

Difficulty:

Medium

Background

Studio learning is a “signature pedagogy” of contemporary design education with origins in fine arts schools. These days there is a wide range of flavours and practices that characterise design studios, from basic foundation courses to student-led and capstone projects with industry. A critical component of all studio experiences is the “design brief” conveying to students the information and instructions at the starting point of a studio project. In fact, there are limited sources available to inform design educators how to prepare design briefs that work well. Great design briefs are aligned with the learning outcomes in the syllabus, they set the stage for students to showcase their skills, they offer dimensions for individual and team assessment, and in addition to that, they are attractive, engaging, and memorable (Heller and Talarico 2009).

This recipe is aimed at design educators to support their creative and informed process of (re)defining their studio briefs in a range of situations, including remote learning in these times of physical distancing and lockdowns. The recipe is structured along twelve lenses to prepare design briefs: Stage, Interpretation, Authenticity, Learning, Affectivity, Orientation, Prescription, Information, Representation, Outcomes, Assessment, and Execution -Figure 1.

Ingredients

- Studio learning outcomes

- Information about students including skills and interests

- Assessment criteria and rubrics

- First-hand design experience

- External partnership (optional)

Method

- Start by analysing your previous briefs, and if possible, the briefs of others. You can form your own collection of briefs used in education, or from industry or design competitions. Do analyse what makes these briefs interesting or appropriate, and avoid directly copying a brief just because you liked it or it worked well before. Instead, develop an analytical eye for briefs and try to extract principles that make briefs more or less appropriate for a given learning scenario.

- Use the twelve lenses (Figure 1) to examine existing briefs. Not all dimensions will be relevant for every brief, so work with those that feel more applicable. These 12 lenses are also used to tweak or transform a brief, and to create a new brief from scratch. Use the following questions to analyse and synthesise a brief through each lens:

- Stage: What are the aspects of this brief that make it more/less restricted? Is this brief staged to prioritise creative and imaginative thinking, or a specific set of tools or skills? Does the brief have precedent solutions that will influence how the students’ outcomes are assessed? What aspects of the brief are students allowed/encouraged to change? Is the brief staged in a single or multiple phases?

- Interpretation: How does this brief allow/restrict interpretability of its intended problem formulation, constraints, requirements, and outcomes? What level of skills, knowledge and experience does this brief require? What is the degree of vagueness and ambiguity conveyed by this brief?

- Authenticity: How realistic does this brief need to be for its target audience and the learning outcomes of this course? What aspects of this brief are likely to be meaningful and engage students? What are the expectations set by this brief in terms of resources, time, and student interest? Is this brief relevant today and for this generation of students, or how well has it aged? Is the brief connected to current events?

- Learning: What are the instructional qualities of this brief? What aspects of this brief support student-led learning and which ones require more directed instruction? Where does this brief place the emphasis between the design process and the design outcome? How does the brief accommodate for formative and summative assessment, peer feedback and design crit sessions including with external stakeholders?

- Affective: What aspects of this brief make it interesting, challenging, thought-provoking? What emotions is this brief likely to trigger in students? Is it a culturally appropriate brief? May privacy or other sensitive issues merit ethics review?

- Orientation: How is this brief likely to shape the relationships in the learning environment? Does the brief promote collaboration or competition between individual learners and/or teams? How is this brief shaping what students can do outside the classroom? Do they need to conduct field visits, engage with external experts, is this brief safe for students?

- Prescription: What aspects of this brief are nomological and what aspects are negotiable? To what extent does the brief set the student to success or failure? What are the variations expected or encouraged across individual or team outcomes in the classroom? Does the brief make a clear distinction between the means and the ends of this project? May the brief prime students or bias their responses inadvertently?

- Information: How much and what information does the brief contain? How much and what information are students expected to research from primary and from secondary sources? Will required or optional information be made available in stages? May the learning outcomes allow for instructors to make changes to the brief mid-way through the semester?

- Representation: What formats are used to present the brief to students? Oral, written, visual, physical samples, etc? How does the format of the brief affect its qualities as viewed through the other lenses? Does the brief need to be refreshed?

- Outcomes: What are the design outcomes and the learning outcomes required by this brief? Are these two types of deliverables well aligned, or are there intentional or unintentional discrepancies?

- Assessment: How are the criteria of success conveyed in the brief? Is it clear to students how the assessment may incorporate effort and results? How does the brief allow for responses that meet and even exceed expectations?

- Execution dependency: How original is the brief? What aspects may make this brief deceptive or misleading, such as “Trojan horse briefs” as noted by Heller & Talarico 2009, p. 13? Where does this brief put the burden in the design process: briefs that require more initial conceptual exploration vs. briefs that require more careful crafting and polished final outcomes.

- Continually iterate and test different versions of a brief by sharing them with colleagues in academia and industry, former students, or friends. Learn from their feedback and be open to change your briefs when necessary. Test your briefs yourself by using them to design possible solutions and to anticipate problems and opportunities.

- As you feel more confident and narrow down a few options, recruit a small group of volunteers to conduct a “dry-run” where you can test your briefs by noticing the design ideas created. It may be the case that changes in some of the twelve characteristics noted here do not have a noticeable impact, but do expect small changes to have potentially major effects on how students understand, accept, interpret, engage with, and respond to a design brief in studio.

- When you are ready to deploy the brief in a studio project, be mindful of how it works the first few times. Gather feedback from students specifically about the brief, including during a project and in post-mortem sessions with all or a segment of the class. Take notes and register new possibilities for the next time you use this brief.

- When grading student work in studio, pay attention to how the brief may have influenced the outcomes created by students. Conduct post-moderation with colleagues and, if student evaluations are available, look for issues that may be directly related to and resolvable through how the brief is designed.

- Share your briefs. Include your colleagues in reflection sessions, share ideas and lessons learned with other studio instructors, particularly junior instructors and teaching assistants. Document your briefs and write blog posts, make your briefs and your experience using briefs publicly available. Inform your analysis and reflections with the vast literature from learning sciences and learning philosophy.

Notes on ingredients

Here are a few briefs available online to get you started:

- The Marshmallow Challenge is a 18-minute activity with a highly constrained brief as presented by Tom Wujec: https://www.tomwujec.com/marshmallowchallenge

- The Dyson Award has a minimal brief: https://www.jamesdysonaward.org/

- The Braun Prize looks for conceptual designs: https://www.braunprize.org/

- The Index project breaks the conventional design categories and focuses on impact: https://theindexproject.org/award

- A portal of student design competitions: https://studentcompetitions.com/

Other flavours:

Some design schools (unfortunately not enough to my knowledge) use student-led briefs in studio projects. In that case, the transitioning from earlier studios needs to include students in the reflection process about what makes a great brief, so that by the time they are in charge of their own briefs, they can analyse and prepare good quality briefs.

Warnings:

Recipes are meant to have an end product, but this recipe invites you to keep evolving your briefs in a continuous journey of testing new ideas and sharing with the wider community. A major challenge in studio pedagogies is always assessment, a separate recipe will look at assessments including self and peer, as well as individual vs group contributions in a team project.

References

Heller, S., & Talarico, L. (2009). Design School Confidential: Extraordinary class projects from international design schools. Beverly, MA: Rockport Publishers.

Shulman, L. S. (2005). Signature pedagogies in the professions. Daedalus, 134(3), 52-59.

Sosa Medina, R. (2019, 2019/11/21/). Qualities of Design Briefs for Studio Learning. In N. A. G. Z. Börekçi, D. Ö. Koçyıldırım, F. Korkut, & D. Jones (Chair), Symposium conducted at the meeting of the International Conference for Design Education Researchers, Ankara. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.21606/learnxdesign.2019.09005

]]>This article is based on an online presentation delivered on 22 May 2020 for the Teaching Architecture Online: Methods and Outcomes seminar, organised by Curtin University and Özyeğin University, titled ‘Responsive Ecosystems for Architectural Education’ (Morkel & Delport, 2020). In this article, we propose that, rather than the on-ground-online binary, architectural education might be conceived as an ecosystem-of-learning. We further suggest that this ecosystem-of-learning can be explored through the testing of random concepts to prompt and provoke a shift in thinking.

Introduction

Covid-19 exposed the fragility of schools of architecture, affecting carefully integrated curricula, student experiences and teaching methodologies. We position this integrated learning approach as an ecosystem-of-learning comprised of a number of elements including those shown in Figure 1.

Social distancing forced some parts of the default ecosystem to change drastically and suddenly, and this impacted on the entire ecosystem-of-learning. Access to physical buildings, studios, and workshops was lost. The place dimension of the learning system changed (figure 2). Where, before, time was carefully divided into segments on a timetable, organising the occupation of physical space, suddenly the timetable itself became obsolete.

‘Higher education institutions must prepare for an intermediate period of transition and begin future-proofing for the long term’ proposed DeVaney et al. (2020). So we’re asking: how might we shift our gaze to the longer term, to move online architectural education beyond “emergency remote teaching” (Hodges et al., 2020), from ‘contingency to sustainability’ (Salmon, 2020)?

Yet, what we’ve observed in webinars, blog posts, forums and research writings over the past number of weeks, are questions asked about the uncertainty and unpredictability of the situation. In the process of adapting to a new condition, there’s a degree of vulnerability, concerns arising over inequality and access, the loss of touching paper, building models, the physical making together, the incidental moments of discovery, the informal and social learning instances, the camaraderie and the fun – these experiences have been ‘lost’ through mandatory social distancing and the resultant altered dimensions of space and time.

Is a reset possible?

Darren Ockert (2020) writes that ‘(e)ach day during the pandemic, we are suddenly finding what was once impossible is now suddenly possible.’ He quotes Thomas Friedman, who said of online learning in 2012 ‘Big breakthroughs happen when what is suddenly possible meets what is desperately necessary.’

We believe that a reset is possible, but through ‘step(ping) beyond the obvious and rethink(ing) how we think’ (Weyler, 2020).

What next?

To use the crisis as a catalyst for innovation, as suggested by O’Reilly (2020), we turn to the ecosystem-of-learning as a metaphor. An environmental ecosystem is defined as a ‘complex of living organisms, their physical environment, and all their interrelationships (are) in a particular unit of space’ (Merriam-Webster, n.d.). Considering learning as an intrinsically human activity that occurs in many places and in different ways (Rustici, 2018) we conceptualise an ecosystem-of-learning that involves the tools, technologies, resources, the people and the places where learning happens.We chose ecosystem over ecology as a framework because, compared to ecology which describes a universal idea, an ecosystem is associated with a specific context (Merriam-Webster, n.d.).

A different way of thinking might embrace diversity in the way that Rex Weyler (2020) suggests: ‘Diversity remains a value in an ecosystem because diversity enhances stability.’ He further explains that ‘an ecosystem prospers if it is simultaneously stable and flexible, conservative and progressive’ (Weyler, 2020).

To demonstrate how a shift in thinking might be prompted, we draw on a range of random concepts to generate questions (Hitge, 2016; Kayton, 2011). These questions are borrowed from six domains, as thinking prompts, to reshape architectural education for the future. The selected domains are educational, economic, environmental, social, technological and political domains; each explored through three randomly selected conceptual question prompts.Of course the question prompts and resulting exploration will have varying results, depending on the participants. For example, some prompts may be more relevant to management, others to faculty or students. Furthermore, for each of the prompts (the list is not extensive), different viewpoints should be taken.

In a recent online lecture, entitled ‘How Limitations Boots Creativity’ Ingwio D’Hespeel from the LUCA School of Arts in Belgium, reimagined the traditional PowerPoint and presented his talk with a ‘paperpoint’. The low-tech, low-budget and low-resource paperpoint brings aspects of the interactive and the hand-made into the online space.

We hope that the thematic conceptual prompts that we introduce below, can trigger similar creative, relevant and realisable reactions to inspire the development of a responsive and resilient ecosystem-of-learning for architectural and design education.

Educational prompts

How might pedagogy of care, universal design for learning and flux pedagogy help us shift our thinking towards a responsive, resilient and relevant ecosystem-of-learning for architectural education in these times of change, uncertainty and unpredictability?

- Pedagogy of care is a concept that stresses contribution and empathy. Cormier (2020) asks ‘how can we balance the care that we give our students and the care that we give to ourselves?’ He invites us to imagine the first five minutes of class – the smiles, the eye-rolls and the catch-ups, and to think about ways to do that online.

- Universal design for learning, according to Morin (2020), ‘is a way of thinking about teaching and learning that gives students an equal opportunity to succeed’, through the flexible use of a variety of teaching methods to remove any barriers, and respond to every student’s strengths and needs.

- Flux pedagogy is a term recently coined by Sharon Ravitch (2020), and it integrates ‘relational and critical pedagogy frameworks into a transformative teaching approach in times of radical flux.’ She explains that it is ‘a humanizing pedagogy that examines the goals and processes of education in moments of uncertainty with a goal of mutual growth and transformation.’ Also, refer to Beatty’s (2019) Hybrid-Flexible (HyFlex) Course Design.

Economic prompts

How might sharing economy, phygital marketing and the gig economy help us shift our thinking towards a responsive, resilient and relevant ecosystem-of-learning for architectural education in these times of change, uncertainty and unpredictability?

- Sharing economy. The sharing economy or Uberfication marks a prominent ‘societal shift’ in which ‘state-regulated service providers like hotels and taxi companies, are replaced by information and data management intermediaries, like Airbnb… and Uber’ (Hall, 2015).

- Phygital marketing. Phygital (also known as phygital) merges the ‘online and offline environments’, taking the ‘best aspects from each space to create an improved customer experience.’ For example, using technology on multiple platforms to build on the ‘immediacy, immersion, and interaction’ of the real bricks and mortar experience (Ames, 2019).

- Gig economy. The concept of the gig economy has been around for a while, with specific reference to the manner in which people work. It can be broadly defined as “a labour market made up of freelance, short-term and on-demand work…which…redefines the way companies hire and how individuals structure their careers (Investec, 2019).

Environmental prompts

How might regenerative design, permaculture design and environmental sociology help us shift our thinking towards a responsive, resilient and relevant ecosystem-of-learning for architectural education in these times of change, uncertainty and unpredictability?

- Regenerative design, which, as a general concept, is a ‘principle that calls for products or services to contribute to systems that renew or replenish themselves. This ultimately means the materials and energy that go into a product or process, can be reintroduced into the same process or system, requiring little to no inputs to maintain it’ (Wbcsd, 2020).

- Permaculture design, although far from a new concept, has 12 key principles that ‘opens into whole systems thinking’ and are ‘thinking tools, that when used together, allow us to creatively re-design our environment and our behavior in a world of less energy and resources’ (Holmgren and Telford, 2020).

- Environmental sociology is concerned with the ‘reciprocal relationships between environment and society.’ The concept acknowledges that ‘environmental issues (we could also read here educational issues) are socially constructed in ways that need to be understood if effective and just strategies for dealing with them are to be found’ (Lockie, 2015:139).

Social prompts

How might fun theory, social presence theory and compassionate collaboration help us shift our thinking towards a responsive, resilient and relevant ecosystem-of-learning for architectural education in these times of change, uncertainty and unpredictability?

- Fun Theory. If you want to get people to change their behaviour you must make what you want them to do, novel and fun, according to Wickes (2018). That’s Fun theory – it’s as simple as that.

- Social presence theory. Social presence theory (presence vs attention) is used to understand how people socially interact in online learning environments. Researchers like Whiteside, Dikkers and Swan (2017) define social presence in terms of being a “real” person, where others define it as feeling a connection or sense of belonging with others.

- Compassionate collaboration. Sir Ken Robinson refers to compassionate collaboration and he means compassion that is ‘fundamental to our ability to be together as communities, as the sort of cultural glue that holds us together …’ (Hall, 2017).

Technological prompts

How might human-computer interaction, bioinformatics and makification help us think about a responsive, resilient and relevant ecosystem-of-learning for architectural education in these times of change, uncertainty and unpredictability?

- Human-computer interaction. Dickson (2017) posits that “(t)hanks to advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning, a slow but steady transformation is coming to education…’ and he says that it forces us to consider what it means to be human.

- Bioinformatics. Ben Williamsen (2020) references socio-genomics and geno-economics that link the study of genomics with predicted socio-economic outcomes through the power of big data and bioinformatics infrastructures.

- Makification. Cohen, Jones, Smith & Calandra, (2017:3) writes that ‘simply put, we define makification as the process of taking characteristic elements from the maker movement and infusing them into formal educational activities in a variety of contexts.’

Political prompts

How might cultural citizenship, development theory and the entrepreneurial state help us shift our thinking towards a responsive, resilient and relevant ecosystem-of-learning for architectural education in these times of change, uncertainty and unpredictability?

- Cultural citizenship. According to Van Hensbroek, ’cultural citizenship, psychologically and ideologically connects members within a community, or members of different communities through a sense of common belonging, reciprocal recognition of belonging, and shared experiences of daily life’ (Van Hensbroek, 2010: 317).

- Development theory. ‘Development theory is a collection of theories about how desirable change in society is best achieved’ (Gallagher, 2016: 260).

- The Entrepreneurial State. In her controversial book, ‘The Entrepreneurial State’, Mariana Mazzucato reveals that, contrary to popular belief, the state is, and has been, our boldest and most valuable innovator, e.g. in the pharmaceutical industry. Almost every medical breakthrough starts in publicly funded laboratories.

Conclusion

As the emergency subsides but normality fails to return, higher education institutions must consider a reset. There’s a good likelihood that virtual learning – in some form or another – will be part of education for the foreseeable future. Coalescent spaces for learning are inevitable (White, 2016), but exactly how this plays out, will depend on the degree to which we are able to rethink and reconceptualise the different elements of the ecosystem and how they relate.

We hope that our exploration will prompt further thinking and debate towards a responsive, resilient and relevant ecosystem-of-learning for architectural education in these times of change, uncertainty and unpredictability. Considering architectural education as an ecosystem-of-learning can help us move beyond the on-ground-onsite binary towards a dynamic but balanced, ecosystem.

This is work in progress and we invite your comments and suggestions.

Postscript

We both studied at a traditional University in the Eastern Cape of South Africa. The University of Port Elizabeth was, at the time, operating very much like most universities today, although we graduated even before the computer made it into architecture as a tool for drawing. After a few years in practice, we both started teaching, almost at the same time, at the Cape Technikon. There, architecture was taught from a technological perspective, so, from the start of our academic careers, we taught differently to how we had been taught. We both started writing about our teaching practices when the Technikon became a University and formal research was introduced, focusing on alternative places of learning (other than the studio). We tested our respective research ideas in the second year studio, where students were involved in academic and work-based learning components. Starting in 2010, together with our students, we crafted this studio into an online and onsite model to expand the on-campus studio. The online explorations included learning through digital storytelling, wayfinding using QR codes, virtual tutors, etcetera. During the block weeks, we met physically with our students, where they participated in interactive and hands-on exercises, such as experimenting with natural building methods, developing designs through physical model building and completing design-build projects in communities. In-between the block weeks, students were supported at their places of work, online, through various social media platforms, a course blog, feedback via podcasts and screencasts, reflection through blogging, and online desk crits using skype. These ideas led to other blended and online programmes, for example, the part-time BTech programme offered by the CPUT in collaboration with Open Architecture.

*Dr Hermie Delport is the Programme Leader: Architecture and Spatial Design at STADIO Holdings

The diagrams

In our search for literature on ecosystems, after we had formulated the ecosystem diagrams (figures 1, 3 and 4), we serendipitously found the Sacramento startup and innovation ecosystem diagrams (Bennett, 2016). The potential of this ‘circuit board diagram, aka subway map’ diagramming method to describe and compare ecosystems-of-learning, should be further explored.

References

Ames, C. 2019. Blurring the line between Physical and Digital. https://www.emotivebrand.com/phygital/

Beatty, B. J. (2019). Hybrid-Flexible Course Design: Implementing student-directed hybrid classes (1st ed.). EdTech Books. Retrieved from https://edtechbooks.org/hyflex

Bennet, J. 2016. Sacramento startup and innovation ecosystem diagram update. [online]. Accessed via https://startupsac.com/sacramento-startup-and-innovation-ecosystem-diagram-update/

Bregman, R. 2020. The neoliberal era is ending. What comes next? https://thecorrespondent.com/466/the-neoliberal-era-is-ending-what-comes-next/61655148676-a00ee89a

Cohen, J., Jones, W.M., Smith, S. & Calandra, B. 2017. Makification: Towards a framework for leveraging the maker movement in formal education. Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia. 26(3):217–229

Collins Z., Holum A., Seely Brown J. 1991 Cognitive Apprenticeship: Making Thinking Visible http://www.21learn.org/archive/cognitive-apprenticeship-making-thinking-visible/

Cormier, D. 2020. Move to Online Learning: 12 Key ideas. Move to Online Learning: 12 Key Ideas – Dave’s Educational Blog http://davecormier.com/edblog/2020/05/17/move-to-online-learning-12-key-ideas/

Costanza, R., Mageau, M. 1999. What is a healthy ecosystem?. Aquatic Ecology 33, 105–115 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009930313242

DeKay, M. 1996. Systems thinking as the basis for an ecological design education. Proceedings of the 21st National Passive Solar Conference. Systems Thinking as the Basis for an Ecological Design Education. School of Architecture Washington University St. Louis.

DeVaney, J. Shimson, G. Rascoff, M. and Maggioncalda, J. 2020. Higher Ed Needs a Long-Term Plan for Virtual Learning. Harvard Business Review. [online]. Available at: https://hbr.org/2020/05/higher-ed-needs-a-long-term-plan-for-virtual-learning

D’Hespeel, I. 2020. How Limitations Boots Creativity. Online presentation on 20 April 2020, Greenside Design Centre Lockdown lecture series.

Dickson, B. 2017. How Artificial Intelligence Is Shaping the Future of Education. https://www.pcmag.com/news/how-artificial-intelligence-is-shaping-the-future-of-education

Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/ecosystem

Gallagher, S. 2019. Banking Performance and Socio Economic Development. ED – Tech Press, Essex.

Hall, G. 2015. Post-Welfare Capitalism and the Uberfication of the University II: Platform Capitalism. http://www.garyhall.info/journal/2015/4/28/post-welfare-capitalism-and-the-uberfication-of-the-universi.html

Hall, R. 2017. Surviving in the Modern World: In conversation with Sir Ken Robinson. https://www.ashoka.org/en-gb/story/surviving-modern-world-conversation-sir-ken-robinson

Hitge, L. 2016. Cognitive apprenticeship in architecture education: using a scaffolding tool to support conceptual design. University of Cape Town.

HMC Architects, 2020 https://hmcarchitects.com/news/regenerative-architecture-principles-a-departure-from-modern-sustainable-design-2019-04-12/

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T. and Bond. A. 2020. The Difference Between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning. Educause Review. [online] Available at: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning

Holmgren and Telford. 2020. Permaculture Principle [online] Available at: https://permacultureprinciples.com/principles/

Investec. 2019. Rocking the gig economy [online] Available at: https://www.investec.com/en_za/focus/economy/rocking-the-gig-economy.html

Lederman, D. 2020. The HyFlex OPtion for Instruction if Campuses Open This Fall. [online] Available at: https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2020/05/13/one-option-delivering-instruction-if-campuses-open-fall-hyflex

Lockie, S. 2015. What is environmental sociology?. Environmental Sociology 1:3, pages 139-142. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23251042.2015.1066084

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Ecosystem. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved June 1, 2020, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ecosystem

Morin, A. 2020. What is Universal Design for Learning (UDL)? https://www.understood.org/en/learning-thinking-differences/treatments-approaches/educational-strategies/universal-design-for-learning-what-it-is-and-how-it-works

Morkel, J. and Delport, H. (2020). Responsive Ecosystems for Architectural Education. Online presentation for the Seminar Teaching architecture online 2. Methods and outcomes, 22 May 2020. [online]. Available at: https://youtu.be/q5y6puwYFng [31 May 2020].

Ockert, D. 2020. What Coronavirus can Teach Architecture Schools about Virtual Learning. https://www.archdaily.com/938784/what-coronavirus-can-teach-architecture-schools-about-virtual-learning

O’Reilly. 2020. Don’t let a good Crisis go to waste. Instead use it as a catalyst for innovation. https://singularityhub.com/2020/05/03/dont-let-a-good-crisis-go-to-waste-instead-use-it-as-a-catalyst-for-innovation/

Patrick Kayton – Going With The Flow (2011) YouTube video added by TEDxCapeTown Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r8T7FYTiXKI [Accessed 1 June 2020].

Ravitch, S. 2020. Flux pedagogy. Transformative Teaching in the time of Corona. [online] Available at: https://www.methodspace.com/flux-pedagogy-transforming-teaching-learning-during-coronavirus/

Rustici, M. 2018. An Introduction to Modern Learning Ecosystems. https://www.watershedlrs.com/blog/learning-data-ecosystems/what-is-a-modern-learning-ecosystem

Salmon, G. 2020. Covid-19 is the pivot point for online learning. Whonke. [online] Available at: https://wonkhe.com/blogs/covid-19-is-the-pivot-point-for-online-learning/?fbclid=IwAR3vxMkUXrOTwqqE2aVdeJghoNb3PIyGLVT2UsqBMS4heNUs8SFY5cQAiq4

Steward, S. 2020. Five Myths about the Gig Economy. The Washington Post [online]. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/five-myths/five-myths-about-the-gig-economy/2020/04/24/852023e4-8577-11ea-ae26-989cfce1c7c7_story.html

Tomboc, K. 2019. What is Information Design. https://www.easel.ly/blog/what-is-information-design/

Van Hensbroek, PB. 2010. Cultural citizenship as a normative notion for activist practices, Citizenship Studies, 14:3, 317-330, DOI: 10.1080/13621021003731880

Wbcsd. 2020. Circular Economy Programme. [online] Available at: https://www.ceguide.org/Strategies-and-examples/Design/Regenerative-design

Weyler, R. 2020. Ecological imperatives – we can’t keep growing like this, [online] Available at: https:www.greenpeace.org/international/story/43513/ecological-imperatives-growth-economics-coronavirus-pandemic/

White, D. 2016. Coalescent spaces http://daveowhite.com/coalescent/

Wickes, S. 2018. https://www.familyadventureproject.org/fun-theory/

Williamsen, B. 2020. Datafication and automation in higher education during and after the Covid-19 crisis https://codeactsineducation.wordpress.com/

]]>It took a bit longer than expected (it started out as a blog post but ended up being a 20k word monster!), so there’s a few ways you can use it set out below.

Over the next few weeks I’ll think about other ways to make expand on it and make it more widely available – so any suggestions on this would be welcomed (e.g. blog posts on topics; videos; discussions/debates; workshop sessions; ? ). Just let us know ([email protected]).

Ways to use the guide.

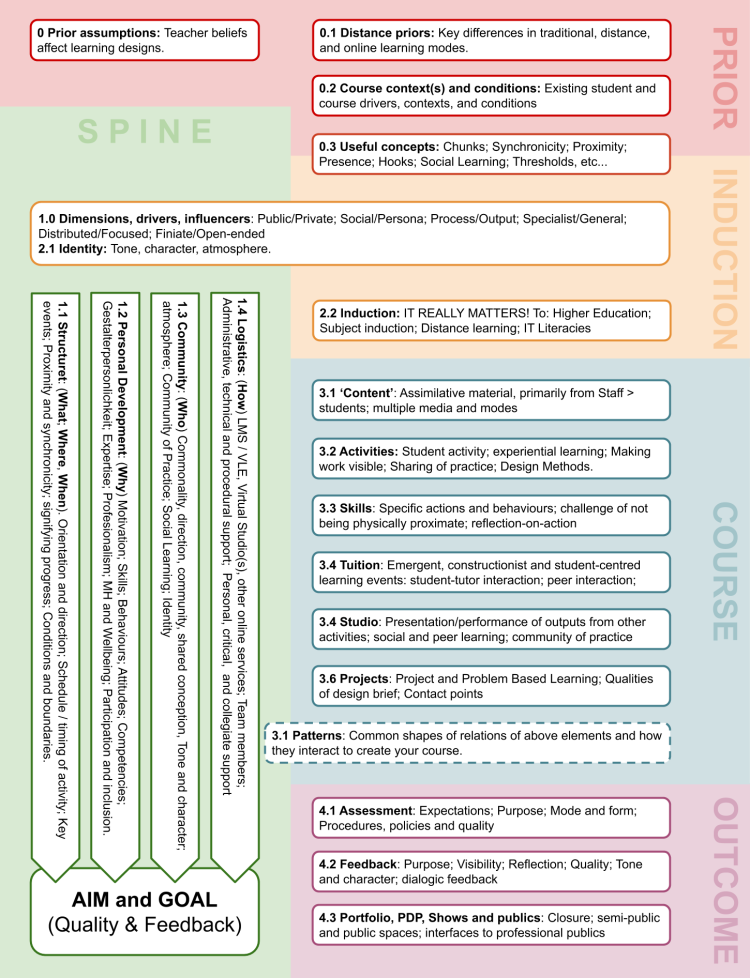

If you already have a course ready for online and distance delivery, you might simply use this guide as a check or list of things to think about. Here’s a map of the contents:

If you have an existing blended course or are experienced and confident in blending modes of learning, you might simply want ideas and ways of thinking about parts of your course. In this case you can refer to individual sections based on what interests you (see map above).

If you need to re-plan an existing course, the chances are your overall structure and direction are fine but that you might need to focus on the transition (or transposition) to online and distance. Focusing on sections 0 Priors and 1 Spine and 2 Induction will likely be of most use to you here).

If you’re needing to start from scratch then, by all means, use the guide to do this (as a structure or as some way to begin the design process). But think about connecting with someone or a community to support you in doing this.

As always, if anyone has any feedback on the Guide or any suggestions of what else would be of help then please just get in touch ([email protected]).

]]>At the time of writing, in early May 2020, most architecture educators have passed through all five stages of the Kübler-Ross model of grief: denial, anger, depression, bargaining, acceptance (Kübler-Ross, 1969). We spent the first two months of the year in a politically-sanctioned period of denial. When it became apparent that the virus was not contained to a specific geographic region or demographic, our governments instigated restrictions and our universities closed. At that point, we entered the phase of anger. Some made it to bargaining and then depression. Those who made it out the other side are emerging with a lukewarm glow of acceptance: we are all distance educators now.

Researchers at Imperial College London have argued that we need two different but interdependent strategies to manage the effects of the virus: mitigation (slowing epidemic spread while protecting those most at risk) and suppression (reversing epidemic growth and maintaining that situation indefinitely) (Ferguson et al, 2020). If followed, the Imperial College model is sobering for teachers. We can expect at least three, perhaps four, periods of social distancing during the northern hemisphere’s 2020/21 academic year – and that’s assuming we return to campus at all.

As we approach the busiest days of the academic year in the northern hemisphere, we have to recognise a fundamental fact: “we’re not going back to normal” (Lichfield, 2020).

The shift to distance education presents a particular challenge for architecture education. Our discipline has been one of the most resistant to fundamental pedagogical change. With fairly dramatic change now imposed upon us, and as our focus shifts from just surviving this year to actively planning next year, there is an opportunity to critically engage with the widely held assumptions of how we teach design in architecture.

Our signature pedagogy

In the United Kingdom, the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) and the Architects Registration Board (ARB) administer the discipline’s professional accreditation. The RIBA Procedures for Validation and Validation Criteria have, since their revision in 2011, explicitly prescribed that the assessed work of undergraduate and taught postgraduate courses in architecture “should consist of at least 50% design studio projects” (RIBA, 2014, p. 5). Not design projects, but design studio projects. The gatekeepers of the profession in the UK specify not only a minimum quota of design education but also an inconsistently interpreted method of delivery.

A survey of the 63 validation reports of UK architecture schools published by RIBA between 2014 and 2019 finds 25 instances of references to “studio culture”, either in the commendations by the board that visited the school of the academic position statements written by the heads of schools.[1]

These academic position statements include phrases such as “central to our programmes is a strong and vibrant studio culture,” (RIBA, 2017a, p.4) and “in our studio culture we experiment playfully, analyse thoughtfully, apply rigorously and reflect critically… Studio culture provides the safe, inclusive environment in which students can take risks and increase in confidence.” (RIBA, 2020, p.4)

Another statement reads that “central to the ethos of the school is the vibrant studio culture, which is the foundation of the student experience and emphasises a culture of the craft of making integrated with digital design … Design studio is seen as a place for the exchange of ideas where students learn from each other as well as staff and visiting scholars and practitioners.” (RIBA, 2016, p.3)

The design studio is clearly a pervasive learning environment. It is also one that absorbs students far beyond their scheduled contact hours. One school writes how “the 24-hour access to these studios plus the open kitchens has engendered a strong connection between students on all programmes.” (RIBA, 2017b, p.4) Likewise, the commendations of another report congratulate a programme team for inculcating students to treat the studio not just as a place of study, but a place of continuous occupation, where (with my emphasis) “students in the school had unselfconsciously created a genuine live-in studio culture in their main building.” (RIBA, 2017c, p.6)

In these documents we can see how the design studio can be variously celebrated as “a place to study and work in a highly creative multi-disciplinary environment alongside dance, art, design and music studios” (RIBA, 2018, p.3) or criticised as a dangerous site of intermingling with non-architects. The action point of a report observes (with my emphasis) “that the social and cultural environment of architecture in the studios needed to be carefully nurtured, and that too much diffusion of the subject area across the campus might have unintended consequences.” (RIBA, 2017c, p.6)

The design studio is architecture’s signature pedagogy. Lee Shulman defined the concept of signature pedagogy as “types of teaching that organize the fundamental ways in which future practitioners are educated for their new professions.” The design studio in the architecture school is a perfect example of how, Shulman writes, signature pedagogies “even determine the architectural design of educational institutions, which in turn serves to perpetuate these approaches.” (Shulman, 2005, p.54)

Yet the design studio is a complex and multi-dimensional thing. It is the site of both innovation and uncritical replication. It is home to both critical pedagogies that liberate students and uncritical teaching methods which demand their submission to old fashioned ways.

The four dimensions of the design studio

One way to understand the design studio, it is necessary to comprehend what I call its four characteristic dimensions. These dimensions are related to but distinct from the four learning constructs of studio education that Donald Schön described in Educating the Reflective Practitioner (1987): a physical space or constructed environment for learning and teaching; a mode of teaching and learning; a program of activity; and a culture, created by students and studio teachers working together. Schön writes how the design studio is defined by any one-or-more of these constructs, but I would argue that the four cannot be considered in isolation.

Firstly, the design studio is a physical space in the now-shuttered campuses of higher education. How many other disciplines continue to defend the right of an undergraduate student to be provided with their own desk and a working environment on campus, twenty-four-seven for the duration of their studies? In many institutions, therefore, it is the site of a conflict between the traditions of the discipline and the economic pressures of the contemporary university.

Many recent reactions to the shutdown of higher education have come from those educators who regard the space of the architecture design studio as fundamental to the “slightly odd” teaching methods of architecture education. Published in the weeks immediately following the lockdown, one architecture educator writes that “our students rely on having physical and intellectual spaces on campus in which to work. They need access to a well-lit, well-resourced model-making workshop. They require computers they cannot afford themselves. They need each other — students need to be able to rely on their peers if their home environments don’t support our much-loved but slightly odd pedagogical methods.” (Lappin in Sadler et al, 2020)

Secondly, the design studio is a period of time in the teaching calendar. With continuous access to their own learning space, the timetable of an architecture student before the coronavirus pandemic will have also included one or maybe two days per week that were simply ascribed to “studio” – the indeterminate catchall for the time when a student is expected to be present and engaging in either self-directed or directed learning. Many schools of architecture have interpreted the RIBA validation condition of fifty per cent of the curriculum being delivered through design studio to mean that fifty per cent of a student’s schedule must be designated as “studio” time.

In recent weeks, architecture educators who have described their adaptation to “pandemic teaching” have mourned the loss of this collective time. Despite invoking Jeremy Bentham’s eighteenth-century prison one educator writes:

The design studio, however panoptical, offers more than a physical infrastructure that allocates equal desktop space. It offers common hours through which skills sets, expertise, energy, motivation and/or inspiration are in constant flux and are thereby permanently redistributed. A shared studio impedes sorting into the haves and have nots … The very physicality of studio space enables regulation of common standards against the logic of competition … just as the fixed parameter of 12 studio-hours per week can help level the ground between those rich in hours and those disadvantaged by day-jobs or dependents. (Roddier in Pries et al, 2020) [2]

Thirdly, the design studio can be understood as a large field of both teaching method and pedagogies. These are not the same thing. Within the indeterminate time ascribed to “studio” in the calendar, anything goes. The more creative and critical architecture educators deliver radical pedagogical activities, teaching that is informed by educational theory and political agenda. These include collaborative workshops, peer-to-peer learning, blends of asynchronous and synchronous teaching, flipped classroom exercises, experiential learning or live projects with real clients to name just a few. Yet in the darker corners survives the studio where students endure the same old corrupt banking model of education that the tutor learned about as a student. This approach relies on repetition, replication and duplication, and I would argue this distinguishes it as a teaching method rather than a pedagogical approach.

The fourth and final characteristic dimension of the design studio is its culture. When he proposed at is a learning construct, Schön was referring to the ideas, customs and behaviour that occurs in design studio. We should not forget the other meaning of culture: the cultivation of things like bacteria or cells in an artificial medium. Things grow, both good and bad.

The prejudices of architecture education

Architecture education has long been criticised for the ways in which the design studio is the site par excellence for the perpetuation of a hidden curriculum that prejudices certain individuals and groups, inculcating behaviours, attitudes and value systems (Dutton, 1987; Ward, 1990; Banham, 1996; Groat and Ahrentzen, 1996; Stevens, 1998; Webster, 2006 & 2008; Datta, 2007; Salama, 2010; Brown, 2012; Stratigakos, 2016). Jeremy Till writes that “the world of architectural education is obsessed with what it produces, and in this forgets to examine how it produces.” (Till, 2005, p.166)

More than 30 years ago, Karen Kingsley identified the tendencies of bias against women and exclusion of women’s contribution in the popular architectural history texts (Kingsley, 1988). Around the same time, Sherry Ahrentzen and Linda Groat published the findings of a nationwide survey of architecture educators in the USA. Ahrentzen and Groat identified three characteristics of the climate which was prejudiced against female teachers: the dominance of the star system and gendering of genius; the hidden curriculum of rituals that supported power and hierarchy; the isolationism engendered by the myopic attitude of the architectural act (Ahrentzen and Groat, 1992). Design studios have long been known to “exhibit a well-known academic syndrome, in which students believe that mystery – or the neglect of rational teaching methods – is an indication of the mastery of the instructor.” (Fowler and Wilson, 2004, p. 106)

For many architecture educators the path to revealing and subverting the mechanisms of reproduction of architecture education has been to adopt the philosophies and methods of critical pedagogy, including theorists of educational resistance. Architectural education routinely privileges that which Bourdieu and Passeron first christened cultural capital: the educational or intellectual assets which promote social mobility (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1990 [1973]). Peter McLaren explains:

Students from the dominant culture inherit substantially different cultural capital than do economically disadvantaged students, and schools generally value and reward those who exhibit that dominant cultural capital (which is also usually exhibited by the teacher). Schools systematically devalue the cultural capital of students who occupy subordinate class positions. (McLaren, 2009, p. 81)

Acceptance

In the weeks and months after the closure of the physical spaces of higher education, architecture educators are expressing nostalgia for our signature pedagogy. One writes: “Our experiences with remote learning may prove to be a positive experiment, and we may gain new appreciation for digital tools which can support our regular pedagogies. But there is no place like studio” (Donovan in Baxi et al, 2020).

Comparing how a postgraduate seminar course and an undergraduate design studio had transitioned to online teaching, another writes that “the pivot to online teaching was pretty smooth for the seminar… dare I say, it’s actually working quite well. But for the design studio, the transition has been trickier; for students and faculty it can feel challenging and lonely. We all miss the collective camaraderie, the companionship of the shared space.” (Lyster in Sadler et al, 2020).

We should not presume that just by moving the space of architecture education online it will become more egalitarian. Harriet Harriss warns us that:

If [Massive Online Open Courses] have taught us anything, it’s that online learning environments are not democratic spaces by default. These platforms may allocate each user equal inches of screen space, but simultaneously surrender a window into our otherwise private domestic interiors, revealing often staggering economic differentials between students, while also rendering them vulnerable to racist and other discriminatory attacks (Harriss in Martin et al, 2020).

Frank Weine observed that “traditionally, design has been taught in a studio setting and history has been taught in a lecture room. If we accept that this approach has become ineffectual, how could one conceptualize a new model that is more efficacious? One could propose a reversal, so that history is taught in the studio and design in the lecture room.” (Weiner, 2005, 31). Until now, such opinions have been peripheral to the discourse around architecture education. The idea that we might do it differently have been purely speculative. But today, the world over, architecture educators are actively planning curricula without the design studio.

What the four characteristic dimensions of the design studio in architecture education described above have in common is that none of them are consistently defined. Our discipline has, at its heart, a multi-dimensional thing that is defined in space, time, pedagogy and culture. The physical space of the design studio is generally an open-plan room or sequence of rooms, into which independent study, formal teaching, informal teaching, socialising, eating, drinking, bullying, and even harassment or abuse occurs. The temporal dimension of the studio is likewise a curtain behind which lurks a panoply of teaching and learning: sometimes it’s ground-breaking and creative, often it is derivative and even destructive. The pedagogical dimension of the design studio is equally wide and diverse. The cultural dimension of the design studio is something that is often celebrated but rarely defined, and when it is, it is usually in terms that are as exclusive (of women, minorities, mature students, people of different abilities) as they are inclusive.

The question for the coming autumn is resolutely not how can we recreate the architecture studio online. It is how we can liberate our discipline from the assumption that an ill-defined space, time, pedagogy and culture is the only way to teach design. It is an opportunity to re-construct architecture education in a more critical, inclusive and democratic way.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to James Corazzo, Sarah Kettley, Peter Lloyd, Amanda Monfrooe and Ruth Morrow for their suggestions and guidance.

Notes

[1] Accessed via https://www.architecture.com/education-cpd-and-careers/riba-validation/riba-validated-schools-uk on 5 May 2020.

[2] I note here my strong objection to the presumption that scheduling 12 studio-hours per week is all it takes to correct the academic prejudices faced by students ”disadvantaged by day-jobs or dependents.”

References

- Ahrentzen, S. and Anthony, K.H., 1993. Sex, stars, and studios: A look at gendered educational practices in architecture. Journal of Architectural Education, 47(1), pp.11-29.

- Ahrentzen, Sherry, and Linda N. Groat, 1992. “Rethinking architectural education: Patriarchal conventions & alternative visions from the perspectives of women faculty.” Journal of Architectural and Planning Research: 95-111.

- Anthony, K.H., 2001. Designing for diversity: Gender, race, and ethnicity in the architectural profession. University of Illinois press.

- Banham, R., 1996. “A black box: the secret profession of architecture,” in Mary Banham (ed.) A Critic Writes. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Kadambari Baxi, Matias del Campo, Fadi Masoud, Renée Cheng, Elizabeth Donovan, Carl Smith, Dana Tomlin, Aaron Cayer, Delia Mellis, Huda Tayob, G. Pelin Sarıoğlu Erdoğdu, Nicholas Pevzner, Robin Tremblay-McGaw, Billy Fleming, “Field Notes on Pandemic Teaching: 6,” Places Journal, April 2020. Accessed 05 May 2020. <https://placesjournal.org/article/field-notes-on-pandemic-teaching-6/>

- Bourdieu, P. and Passeron, J.-C., 1990 [1973]. Reproduction in education, society, and culture. Thousand Oaks, CA

- Crysler, C.G., 1995. Critical Pedagogy and Architectural Education. Journal of Architectural Education, 48(4), pp. pp. 208-217.

- Datta, A., 2007. Gender and learning in the design studio. Journal for Education in the Built Environment, 2(2), pp.21-35. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.11120/jebe.2007.02020021

- Dutton, T.A. (1987), “Design and studio pedagogy”, Journal of Architectural Education, Vol. 41 No. 1, pp. 16-25, doi: 10.1080/10464883.1987.10758461.

- Ferguson, N., Laydon, D., Nedjati Gilani, G., Imai, N., Ainslie, K., Baguelin, M., Bhatia, S., Boonyasiri, A., Cucunuba Perez, Z.U.L.M.A., Cuomo-Dannenburg, G. and Dighe, A., 2020. Report 9: Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID19 mortality and healthcare demand. Imperial College London. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25561/77482

- Fowler, B. and Wilson, F., 2004. Women architects and their discontents. Sociology, 38(1), pp.101-119. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0038038504039363?casa_token=dXY0ENBo3c0AAAAA:Ya5mBxdEXUUg8NHshMu6E0MRsHhTd16Xbg4d1yxjQebL89yjEVUhHva9kDn0QaCWHdzbYMjugmHzpQ

- Groat, L.N. and Ahrentzen, S., 1996. Reconceptualizing architectural education for a more diverse future: Perceptions and visions of architectural students. Journal of Architectural Education, 49(3), pp.166-183. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/1425326.pdf?casa_token=8nvxumxwwlcAAAAA:Y-OyMymJrHgEBY9zew1dh_Hdhe5_r52GD6N_xQTIXWJsll9E3NbzHxlUfLaAufUl8N8GdK-wNEE8Mt-cu0CGFaQhngWvv42KOknXE4t6Smn9rbIR3bHl

- Kingsley, Karen. “Gender issues in teaching architectural history.” Journal of architectural education 41.2 (1988): 21-25.

- Kübler-Ross E (1969). On Death and Dying. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Lichfield https://www.technologyreview.com/2020/03/17/905264/coronavirus-pandemic-social-distancing-18-months/

- Reinhold Martin, Susan Piedmont-Palladino, Brent Sturlaugson, Barbara Penner, Harriet Harriss, Judith Rodenbeck, Sandy Isenstadt, Anna Livia Brand, Iman Ansari, Hélène Frichot, Brett Milligan, “Field Notes on Pandemic Teaching: 1,” Places Journal, April 2020. Accessed 22 Apr 2020. <https://placesjournal.org/article/field-notes-on-pandemic-teaching-1/>

- McLaren, P., 2009. Critical Pedagogy: A Look at the Major Concepts. In: A. DARDER, M.P. BALTODANO and R.D. TORRES, eds, The Critical Pedagogy Reader. Second Edition edn. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 61-83.

- Olweny, M.R., 2013. Socialisation in Architecture Education. Olweny, M., 2017. Socialisation in architectural education: a view from East Africa. Education+ Training.

- Johan Pries, Andrew Herscher, Hugh Campbell, Shannon Mattern, Erin Moore, Rasmus Hansen, Frederick Steiner, Mireille Roddier, Mira Schor, Shelly Silver, Charles Davis, Philip Ursprung, “Field Notes on Pandemic Teaching: 3,” Places Journal, April 2020. Accessed 22 Apr 2020. <https://placesjournal.org/article/field-notes-on-pandemic-teaching-3/>

- RIBA, 2014. RIBA procedures for validation and validation criteria for UK and international courses and examinations in architecture. RIBA. Available online <https://www.architecture.com/-/media/GatherContent/Validation-Procedures-and-Criteria/Additional-Documents/ValidationProcedures2011SECONDREVISION2MAY2014pdf.pdf> (Accessed 6 May 2020)

- RIBA, 2016. Report of the RIBA visiting board to the Leicester School of Architecture, De Montfort University. RIBA. Available online <https://www.architecture.com/-/media/files/Governance/Board-reports/De-Montfort-University-Report_confirmed-2016.pdf?la=en> (Accessed 6 May 2020)

- RIBA, 2017a. Report of the RIBA visiting board to the University of Sheffield. RIBA. Available online <https://www.architecture.com/-/media/files/Governance/Board-reports/University-of-Sheffield-2017.pdf?la=en> (Accessed 6 May 2020)

- RIBA, 2017b. Report of the RIBA visiting board to Oxford Brookes University. RIBA Available online <https://www.architecture.com/-/media/files/Governance/Board-reports/Oxford-Brookes-Confirmed-Report-2017.pdf?la=en> (Accessed 6 May 2020)

- RIBA, 2017c. Report of the RIBA visiting board to Newcastle University. RIBA Available online <https://www.architecture.com/-/media/files/Governance/Board-reports/Newcastle-report-Nov2016_for-publishing.pdf?la=en> (Accessed 6 May 2020)

- RIBA, 2018. Report of the RIBA visiting board to the University of Salford. RIBA Available online <https://www.architecture.com/-/media/files/Governance/Board-reports/Salford-BSc-Part-1-2017.pdf?la=en> (Accessed 6 May 2020)

- RIBA, 2020. Report of the RIBA Full Visiting Board to the Arts University Bournemouth. RIBA. Available online <https://www.architecture.com/-/media/26F903ACCC2F4558BBCDD6BBC5051756.pdf?la=en> (Accessed 6 May 2020)

- Schön, D. 1987. Educating the Reflective Practitioner. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Shulman, L.S., 2005. Signature pedagogies in the professions. Daedalus, 134(3), pp.52-59. https://www-jstor-org.proxy.ub.umu.se/stable/20027998

- Simon Sadler, Patricia Morton, Richard J. Williams, Fred Scharmen, Clare Lyster, Marshall Brown, Jeffrey Hou, Sarah Lappin, Jonathan Massey, David Heymann, Frances Richard, “Field Notes on Pandemic Teaching: 2,” Places Journal, April 2020. Accessed 22 Apr 2020. <https://placesjournal.org/article/field-notes-on-pandemic-teaching-2/>

- Stratigakos, D., 2016. Where Are the Women Architects?. Princeton University Press.

- Salama, A.M. and El-Attar, M.S., 2010. Student perceptions of the architectural design jury. Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research, 4(2-3), pp.174-200.

- Till, J., 2003. Lost judgement. EAAE prize 2003–2005, Writings in Architectural Education, 2005, pp.164-181.

- Webster, H., 2006. A Foucauldian look at the Design Jury. Art, Design & Communication in Higher Education, 5(1), pp.5-19.

- Webster, H., 2008. Architectural education after Schön: Cracks, blurs, boundaries and beyond. Journal for Education in the Built Environment, 3(2), pp.63-74. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.11120/jebe.2008.03020063

- Weiner, F., 2005. Five critical horizons for architectural educators in an age of distraction. EAAE prize 2003–2005, Writings in Architectural Education, pp.21-46.

]]>

Jo Berben, Faculty of Architecture and Arts, Hasselt University, Belgium

Steven Feast, Architecture and Interior Architecture, School of Design and the Built Environment, Curtin University, Australia

Introduction

The final design review, also known as the portfolio review or design jury, is a well-established but widely contested practice in architecture and design education (Anthony, 1991; Dannels, 2005; Lymer, 2009; Marie & Grindle, 2014; Oh et al., 2013; Webster, 2007). It is a prominent summative assessment tradition for students to showcase and defend their final design projects, for design tutors to celebrate their teaching results, to inspire and motivate fellow students and to benchmark academic standards. Grading and feedback are provided by internal and external critics or jury panel members, including local and external academics and professionals (Murphy et al., 2012). At some universities, other stakeholders like community representatives are also sometimes invited to serve on the panel of critics or the jury.

Based on current international online conversations among architecture and design faculty, it appears that those who have access to digital platforms are coping reasonably well with the temporary transition to online learning and teaching in response to the Covid-19 crisis (Marshalsey, 2020). However, the upcoming assessment period is being met with unease and apprehension by those faculty and staff who are not accustomed to online methodologies (Salmon, 2020). Care must, therefore, be taken to properly design online alternatives to limit stress and anxiety, to allow fairness without compromising academic standards, and to promote learning.

Many architecture and design schools in the northern hemisphere are preparing for final assessments, but few examples of online final design review models exist. This recipe is the result of three colleagues based in Africa, Europe and Australia, thinking about how to ‘whip up’ the final review online, drawing on their collective experiences of onsite and online architecture education. Curtin University offers onsite and fully online Masters in architecture programs, the Cape Peninsula University of Technology presents a blended undergraduate architecture course with a prominent online component, and Hasselt University has recently moved their onsite Bachelors, Honours and Masters in architecture programs online in response to the pandemic situation.

Online design education relies on the use of multiple synchronous and asynchronous digital technologies and tools. These must be employed through careful consideration of their respective affordances (Salmon, 2020). For example, when moving a final design review online, we suggest that the traditional onsite experience should not be replicated, for example, in a Zoom online session. Not only will this option be data-intensive (Stanford, 2020), but also tiring and overwhelming (Degges-White, 2020). Instead, we suggest that a suitable combination of synchronous and asynchronous onsite and online modes be employed to achieve the desired experiences and required outcomes. This move towards effective and durable online solutions rather than emergency remote teaching (ERT) (Hodges et al., 2020), suggests a shift from ‘contingency to sustainability’ – creating ‘the future in a situation of uncertainty’ (Salmon, 2020). Such a future may require a certain degree of flexibility to move between onsite and online modes, as the circumstances allow.

This recipe is for a sandwich model comprising a synchronous online Review phase in between asynchronous Pre-review and Post-review phases. The Review session takes the form of an online discussion, Q & A or interview, focusing on clarification and feedback, rather than a design presentation. Instead, the student’s work is submitted in a presentation bundle comprising drawings, text and video, prior to the online Review session. Should circumstances allow, the Review session can still be conducted onsite. If not, it can be hosted equally well online. In this case, the Pre-review and Post-review phases remain unchanged. The digital format of student submissions allows for onsite or online Reviews.

Serve to:

Architecture and Design faculty, critics and students

Time:

The overall time required will be comparable to onsite sessions, but time for planning and thorough preparation must also be considered

Cost: Low

Connection: Good

Bandwidth: Medium/High

Difficulty: Medium/High

Ingredients

- Asynchronous communication tools: email or online forums via google docs or an LMS (e.g. Blackboard, Moodle, etc).

- Synchronous communication tools: webinar tools e.g. Blackboard Collaborate, Zoom, Jitsi Meet, BigBlueButton, Google Meet etc. for synchronous online discussion sessions. When selecting the tools, consider university policies on security and intellectual property.

- Production and media sharing tools: StoryMaps, moviemaker, screencast-o-matic, Loom, voicethread, Camtasia etc. to produce presentation videos; and Instagram, issuu, Behance etc. to publicly share students’ work.

Preparation

- Design and plan an optimal workflow, and assign the different roles and responsibilities. The plan should include who communicates what to whom by when. Include a backup plan, for example, in case of connectivity problems, power outage or other technical problems. Assign moderators’ rights to more than one person, but make sure they know how to apply them. Involve students in the design and planning stage and encourage them to take the lead if university policy allows.

- Compile a critic briefing pack. This can include written invitations to critics to participate, the study guide or syllabus, project brief documents, rubrics and assessment guidelines, student grades and mark sheets, a repository of student submissions, the link to the online Review session platform, with instructions, and a Review schedule. Consider whether it is possible, or desirable, to allow students to take the lead here too.

- Compile a student briefing pack. This can include guidelines for the online submission of work, required submission formats for the different components that form part of the presentation bundle (e.g. a thesis document, booklet or poster with high resolution renders of 300 DPI minimum, and a video), maximum file sizes, filename protocols and rubrics. It should explain how the online Review session will be conducted, explaining the roles, responsibilities and rules, as well as the online Review schedule. Students may want to set up a dry run to prepare for the online Review.

- Teachable moments. Online sessions dedicated to the development of specific skills necessary for this assessment method can be offered to students by faculty, fellow students or invited presenters. Topics may include, for example, how to develop a powerful narrative, using drawings only to do so, how to respond to trick questions, how to behave and perform in an interview, how to use online media and platforms, and critical thinking.

Method

Pre-review (asynchronous)

Students submit work in digital format for faculty and critics to study in preparation of the online Review session

In the absence of a live presentation, student submissions should engage multimedia to clearly convey their design intent and process. They can draw inspiration from competition submission formats, like booklets or posters, supported by short (max duration should be specified, say 5 – 7 minutes) narrated presentations or videos. Video submissions can be any suitable combination of a narrated screencast or video, including photos or video of physical models, drawings etc.

Students should submit their work well in advance as agreed with faculty, to allow the critics adequate time to study the material. Submission information including penalties for late or non-submissions etc. should be clear, agreed up front and guided by university policy. Digital work can be submitted on the LMS, Google Drive or another digital repository. Designated faculty should collect the files, collate them and share them with the critics.

The critics, in turn, guided by clear rubrics, should peruse the student work in preparation for the upcoming Design Review. They may choose to assign a provisional mark or decide to leave the grading until the Review session. Whilst working through the student work, critics should record all comments and questions to direct at the students in the upcoming online design Review session.

Review (synchronous)

Students, critics and faculty meet online to discuss the submitted work

Students meet critics and design tutors in an online webinar session (Bush, 2020) to respond to questions and comments, and to clarify where needed, using audio, screen-sharing, on-screen pointing and drawing. The use of the webcam can be limited to the start of the session when the introductions are made.

The session starts with the appointed moderator welcoming participants, explaining the timeframe and protocols. Students get, say, approximately 20 – 30 minutes each, starting with a 2-minute introduction and allowing 5-minute transitions in between. For example, a 2-hour session can accommodate five students. Short breaks in between sessions can be reserved for comfort breaks and marks discussions. Observers may use the chatbox for questions and comments and the session moderator can respond where needed. The moderator must make sure that everyone gets an equal opportunity to engage and contribute, managing permissions of participants appropriately.

This online Review session can be recorded for quality assurance, record-keeping and educational purposes, if allowed by the university and if participants agree. Critics and design tutors finalise their marks, using a clear rubric, and record notes where needed.

Post-review (synchronous or asynchronous)

Finalisation of marks, feedback on the review process and public display of student work

Critics and design tutors meet in breakout online spaces to clarify, compare observations and to discuss marks for finalisation and sign off. This process can also be conducted via email, on completion of the design Reviews.

Critics’ and students’ feedback on the review process and organisation can be invited through short online surveys, to inform future events. The online publication of student work can be via e-book tools or social media. Here, too, students can be invited to take the lead.

Variations

- This sandwich method allows the final design review to be switched reasonably easily between onsite and online modes, as demanded by the circumstances. A flexible approach can lead to more robust assessment design. If it is impossible for students, design tutors and critics to be in the same place at the same time, e.g. when students are based remotely, or during periods of social distancing, the final design Review can be conducted online as described above. Should it be uncertain whether an onsite final review will be possible, the same Preview stage and submission requirements as described above, can be followed. If circumstances change and a final design Review becomes possible and it is preferred onsite, students can verbally present their work bundles using projection.

- Students can share their work with their peers (or publicly via social media) prior to the Review stage, to invite asynchronous feedback to help them prepare for the Review. Public sharing of student work is subject to university rules and policy.

- In times of crisis like the current Covid-19 pandemic, it might be necessary to adopt pass/ fail or outcomes achieved/ achieved well/ not yet achieved grading protocol instead of numerical grades. Depending on the context or circumstances, it may even be necessary to completely reconceptualise the assessment strategy and instruments.

References

Anthony, K.H. (1991) Design juries on trial: the renaissance of the design studio. Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York.

Bush, L. (2020) An Online Teaching Survival Guide. Teaching Innovations and Practices. [online] Available at: https://lccteaching.myblog.arts.ac.uk/an-online-teaching-survival-guide/

Dannels, D. P. (2005) ‘Performing Tribal Rituals: A Genre Analysis of “Crits” in Design Studios’, Communication Education, Routledge, vol. 54, no. 2, pp. 136–160 [Online]. DOI: 10.1080/03634520500213165.

Degges-White, S. (2020) Zoom Fatigue: Don’t Let Video Meetings Zap Your Energy. Some ‘cheats’ to help you beat Zoom fatigue before it beats you. [Online] Available at: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/lifetime-connections/202004/zoom-fatigue-dont-let-video-meetings-zap-your-energy

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T. and Bond. A. 2020. The Difference Between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning. Educause Review. [online] Available at: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning

Lymer, G. (2009) Demonstrating Professional Vision: The Work of Critique in Architectural Education, Mind, Culture, and Activity, 16:2, 145-171, DOI: 10.1080/10749030802590580

Marie, J. and Grindle, N. (2014) How Design Reviews Work in Architecture and Fine Art, Charrette, 1: 36-48.

Marshalsey, L. (2020) The preliminary successes and drawbacks of a turn to distance design studio learning. Distance Design Education. [online] Available at: https://distancedesigneducation.com/2020/04/24/the-preliminary-successes-and-drawbacks-of-a-turn-to-distance-design-studio-learning/

Murphy, K.M., Ivarsson, J., and Lymer, G. (2012) Embodied reasoning in architectural critique, Design Studies, Volume 33, Issue 6. Pages 530-556, ISSN 0142-694X [online] Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2012.06.005

Oh, Y., Ishizaki, S., Gross, M. D. and Yi-Luen Do, E. (2013) A theoretical framework of design critiquing in architecture studios, Design Studies, vol. 34, no. 3, pp. 302–325 [Online]. DOI: 10.1016/j.destud.2012.08.004

Salmon, G. (2020) Covid-19 is the pivot point for online learning. Whonke. [online] Available at: https://wonkhe.com/blogs/covid-19-is-the-pivot-point-for-online-learning/?fbclid=IwAR3vxMkUXrOTwqqE2aVdeJghoNb3PIyGLVT2UsqBMS4heNUs8SFY5cQAiq4

Stanford, D. (2020) Videoconferencing Alternatives: How Low-Bandwidth Teaching Will Save Us All | IDDblog: Instructional Design Tips, Advice, & Trends for Online & Distance Learning | Educational Technology and Online Course Design Help. [online] Available at: https://www.iddblog.org/videoconferencing-alternatives-how-low-bandwidth-teaching-will-save-us-all/

Webster, H. (2007) The Analytics of Power, Journal of Architectural Education 60(3), pp21-27. Doi:10.1111/j.1531-314X.2007.00092.x

Artwork by _mariana_art_

]]>The live note document is here and this also has a capture of the text chat. Please keep adding to this (resources, comments, ideas).

Thanks to all contributors so far and a huge thank you to everyone who took part in the meetup!

The recording is here: